By Luis Cano

Article from Studia et Documenta2018

Abstract

The First Supernumeraries of Opus Dei. The 1948 Workshop: In 1947, Josemaría Escrivá was able to bring about a long-awaited aspect of the founding of Opus Dei: the admission of married members or those wishing to form a family. The crucial step occurred in September 1948, when − after having obtained recognition from the Holy See in that regard − he organized a gathering in which fifteen people took part. That’s where the first Supernumeraries came from. This article focuses on the events from these days, during which St. Josemaría explained many details of the life of Supernumeraries. This reconstruction was made possible thanks to the notes and testimonies of some of the participants.

One of the most important milestones in the history of the work of St Gabriel in Opus Dei, which led to its definitive launch, was the week of study and formation that took place in Molinoviejo (Segovia) from 25 September to 1 October 1948. St Josemaría explained in depth to the fifteen people there what it meant to be a Supernumerary in Opus Dei.

My aim is to reconstruct the message that the founder transmitted to them during that week, making use of the documents we have, mainly the written diary that was kept during those days and the personal memories of those who attended. We have limited ourselves to the sources in the General Archive of the Prelature of Opus Dei, which include notes, letters and personal accounts of several of the protagonists in this article that were put into writing after 1975 for the cause of canonisation of Escrivá. St Josemaría spoke to them on twenty-two occasions, and although we do not have the complete transcript of his preaching, there are some notes written at the time by those who were there, especially by Amadeo de Fuenmayor and Tomás Alvira, which enable us to grasp the general gist of what he said.

Before starting on the main theme, we will talk about the immediate background to that week, especially about the founder’s work to define what a Supernumerary was, from a spiritual and juridical point of view. Then we will look at how the workshop itself unfolded and St Josemaría’s preaching there.

At the end, in the appendix, we include biographical sketches of the attendees. For these short biographical notes, we have used the personal witness accounts, already referred to above, and the obituaries of deceased members that are kept in the General Archive of the Prelature of Opus Dei, as well as other items of public knowledge, excluding other private or public files that would require going beyond the scope of this article.

The Vocation to Opus Dei as a Supernumerary:

The Iter of a new phenomenon

From 1928 on the founder had talked to all sorts of people about holiness in the middle of the world, but it would be another twenty years before he could set out a specific vocational path, recognized by the Church, for married people or others thinking about marrying and forming a family. This was possible thanks to the ecclesiastical approval in 1947, by which married people could join Opus Dei in practice, trying “to live the spirit and apostolate of the institution, without being legally bound to it.” This meant a great step forward because it recognised that married people could become holy in their own state following the spirit of Opus Dei, but it was not enough for St Josemaría; he wanted the Holy See to approve the possibility of full membership for married people in the future, something that was not possible at the time.

Meanwhile, the first Supernumeraries (Tomás Alvira, Víctor García Hoz and Mariano Navarro Rubio) began to receive formation in the spirit of Opus Dei. A note dated November 5, 1947 was sent to all the directors of the centres of the Work asking for details about other possible candidates. People were asked to pray with due intensity for these candidates, without yet saying anything to them, “since, as you know,” the note said, “this is a true vocation.”

In December 1947, Escrivá was trying to delineate in detail what exactly a Supernumerary was and the spiritual attention they would receive. Amadeo de Fuenmayor, who at the time was in Madrid working in the General Council of the Work, helped him in this task. In a letter this same month, St Josemaría wrote:

These Supernumeraries! What great hope I have! Amadeo: with all the work you have been doing, you could make a draft directory for Supernumeraries – which for now would have to be quite rudimentary. And the same for their plans of formation – of six months and of one year would be fine for now – in the same style as the ones for Numeraries I asked for some time back. It would be a good idea to think about preparing the regulations, starting with what the Sacred Congregation has approved, so that we can meet the legal civil requirements when I come back. It would also be good if you prepared three or four talks and went to Valencia, Zaragoza, and Bilbao, etc, to start forming core groups there. Clearly, once the work has started, we can’t let it stop; where it starts, a Numerary should stay there as director, with a Supernumerary as Secretary (we’ll talk later about this: take note), who takes on the material burden of the Delegation.

As we can see here, the task entrusted to Amadeo was to describe the figure of a Supernumerary and to explain it to people in the Work who lived in various cities in Spain. Although up to now the apostolic work had involved mainly students and young people, there were already a number of people they knew who met the conditions needed to be Supernumeraries.

A week later, Amadeo replied with a draft of what Josemaría had asked for. Escrivá responded on 18 December 1947:

To Amadeo: I read your notes on Supernumeraries. They don’t seem audacious enough to me as regards their obligations. I’ll give your notes back to you next week with some specific comments. Anyway, I’ll say now that we cannot lose sight of the fact that we are not talking about the inscription of some gentlemen in a particular association, but rather a supernatural vocationto the life of perfection and apostolate. To be a Supernumerary is a great grace from God!

Let us pause briefly to consider this paragraph. The key word that the founder underlines here is vocation. The Supernumeraries are called to the life of perfection (today we would say, using current terminology, to holiness) and to apostolate like other lay people and priests. This clarification by St Josemaría was important. Since the majority of Supernumeraries came from Catholic Action or other pious associations, the danger existed that they would think joining Opus Dei was like joining one of these groups. As we have seen, this is exactly what St Josemaría wished to avoid when he emphasised that to belong to Opus Dei was a “supernatural vocation,” not “the inscription of some gentlemen in a particular association.”

The canonical teaching and theology of the time tended to identify complete self-giving with the religious life or something equivalent, open only to celibate people. However, for St Josemaría it was clear that in Opus Dei there was “one and only one vocation.” Without getting into comparisons, Opus Dei offered a novel reality in this sense, although during those years there was no shortage of initiatives in the Church that sought to re-energise the Catholic laity and even to offer them a specific spirituality for marriage. For example, we can mention the Cursillos movement (Short Courses in Christianity), which took shape between the end of August 1948 and the beginning of 1949; or the Focolari movement (founded by Chiara Lubich and approved on a diocesan level in 1947), which the member of Parliament Igino Giordani joined. He was the father of four children, the first married member of the Focolari and considered the cofounder of the movement. Also the Equipes Notre-Dame (Teams of Our Lady), which began towards the end of the thirties under the impulse of Father Henri Caffarel, and which published in 1947 their Letter setting out their conjugal spirituality.

Returning to our story, on Christmas Day 1947 St Josemaría wrote again to Madrid: “Amadeo, go back over the project – the draft project – on Supernumeraries. Stress the importance of obedience (one cannot belong to an association without explicit oral permission, noted down in writing in that person’s file), etc...”

As we can see, the founder wanted to emphasise that the vocation to Opus Dei was one of complete self-giving and entailed a real act of obedience. He doesn’t explain the reason behind the rule he mentions here, but we can guess he wanted to prevent people from spreading themselves too thinly or perhaps getting caught up in silly comparisons and envies, or perhaps too the confusion that Opus Dei was just one more association, to which one could dedicate only part of one’s time in between other pious activities, and not a true calling from God that requires a total dedication. So it would be prudent to seek the permission St Josemaría talks about.

On January 1, 1948 he wrote to the three people who had asked to join Opus Dei as Supernumeraries:

To Tomás, Víctor and Mariano. May Jesus look after my children!

My dear three: it is impossible now to write to you individually, but my first letter of 1948 is for you. I am praying hard for you. You are the seed of thousands and thousands of brothers of yours, who will come sooner than we think. How hard and how well we will have to work for the Kingdom of Jesus Christ!

A few days later, the founder would glimpse at last a solution for the problem we are considering here. It happened on a trip to Milan, from January 11 to 16, accompanied by Alvaro del Portillo and Ignacio Sallent. On the return leg to Rome, he exclaimed “They fit!” It was a kind of eureka moment because he suddenly saw how to present to the Holy See the way in which the Supernumeraries would “fit” into Opus Dei as fully incorporated members. As soon as he got back to Rome he wrote to Madrid: “I am working on the whole issue of the Supernumeraries: there will be many great and beautiful surprises! How good Our Lord is! Amadeo, tell those three to entrust my work to Our Lady. I promise them a great joy.”

What was the solution that led him to exclaim “they fit!”? It involved explaining that the Supernumeraries “spend part of their time in the service of the institution itself, and find the means for their sanctification and apostolate in their own family duties, and their professional or work-related tasks; (….) they live the same spirit and, insofar as possible, the same customs as the Numerary members; although they will only be entrusted with tasks that are compatible with their own family obligations and civic duties.

In other words, the difference with respect to Numeraries lay in the degree of dedication to the internal work of Opus Dei. Also, for Supernumeraries the sanctification of ordinary life included “their own family duties,” in addition to the professional and social duties that Numeraries as well sanctified. In other words, to be a Supernumerary meant having the same spirit and vocation, but spending a different amount of time “in the service of the institution.”

This was not merely a clever explanation to get through the approval procedure. In our opinion, the founder himself had received a new light on an essential point of the charism: the unity of vocation. He was overjoyed at this discovery, as he wrote on 29 January 1948 to those in Madrid. “You will see this when I talk to you on my return. I will just say now that an immense apostolic panorama is opening up for the Work, just as I saw in 1928; and all within the strictest canonical rules, something that seemed impossible until now. What a joy it is to be able to do all this in the service of the Church and souls!”

Right away he began preparing the statutes that would have to be added to the Constitution of 1947, to present it to the Holy See “with the aim that, as well as Numeraries, other single or married members of whatever condition or profession could join and be legally bound to the institution.” In the letter of petittion, Monsignor Escrivá emphasised that this meant including something that had been foreseen since the beginning of the Work: “iam a prima ipsius Instituti delinatione.” On 2 February the petition was submitted, and a month and a half later, on 18 March 1948, the Sacred Congregation, with the signature of the secretary Monsignor Luca Pasetto, and the seal of the under-secretary Arcadio Larraona, approved the statutes that had been presented.

Meanwhile, St Josemaría kept on working. On 4 February he wrote to Madrid: “I am going to use this time in Rome to work on everything concerning Supernumeraries: how wide and deep is the channel that is opening up! We need to be saints, and prepare our people better intellectually each day. And we need to have enough priests.”

In the following months, the founder took further steps. He arranged that during the summer everything about Supernumeraries and cooperators would be explained to the Numerary members and he also fixed a time in the summer for the formal beginning of this new phase. “During the summer we will prepare the work with the Supernumeraries, and everything will no doubt be achieved that our Lord wants from these people – from these sons! Laus Deo.”

Among other preparations, a workshop was organised for a number of people who could be asked to be Supernumeraries, as well as for the six who had already said yes.

Those present at the first activity for Supernumeraries

The fifteen people who took part in the activity at Molinoviejo came from a variety of places. Among those who were living in Madrid were four people from Cantabria (Manuel Peréz, Manuel Sainz de los Terreros, Ángel Santos and Pedro Zarandona); three from Aragón (Tomás Alvira, Rafael Galbe and Mariano Navarro Rubio); one from Galicia (Jesús Fontán); one from Castilla (Víctor García Hoz); one from Andalusia (Hermenegildo Altozano) and one from Mallorca (Juan Caldés). Three more came from Valencia (Antonio Ivars, Carlos Verdú and Silverio Palafox), and one from Bilbao (Emiliano Amann). They also had a variety of professional backgrounds. There were two Navy officials and two others with a military law background; three lawyers and a judge; two civil engineers, a teacher, a doctor, a pharmacist, a chemist and an architect. Looking at their later careers, one can say that they were outstanding professionals who left their mark as Christians on their families and friends. Some of them worked hard to begin social works for human advancement. As mentioned above, in the Appendix we have included a brief biography of each one.

Most of them had belonged to Catholic Action or pious associations (as was the case with so many young Catholics at the time) before coming into contact with Opus Dei, and had even held positions of responsibility within them. Five of them had known St Josemaría before the Civil War and had attended activities at the Residence-Academy DYA. Among them were two who had lived as Numeraries for some years and who had lost contact due to the difficult wartime situation. Of the other three, two had attended activities in Ferraz – one as a resident – and a third, Tómas Alvira, had met St Josemaría in Madrid during the war.

Three other young professionals had entered into contact with the Work through the apostolic trips to various cities during the post-war period and had even asked to join as Numeraries, only to realize quickly that this was not their path. Encouraged by the founder, they had waited several years for it to be possible to live the same vocation to Opus Dei in a new way. There was also a group who had received spiritual direction from St Josemaría after the war. Some were already married or St Josemaría had helped them discern their vocation to marriage. Of all those there, only three did not know him personally.

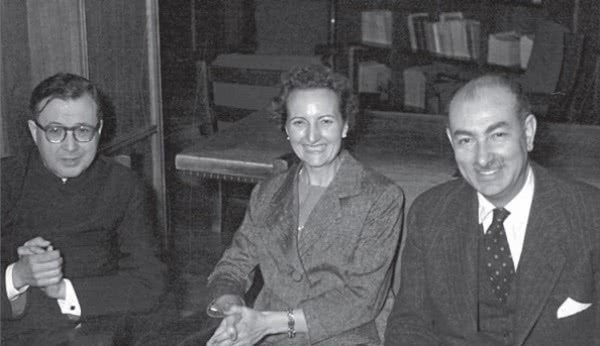

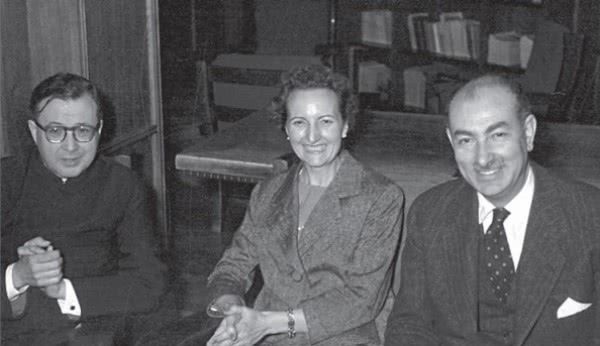

Amadeo de Fuenmayor was present there and we will make frequent use of his diary writings. Introducing those taking part in the pages of this diary, he wrote: “Everyone who said they would come has come. They are mature men, most are married, and a few are already 50. Several have formalised their admission as Supernumeraries, and they all know and love the Work, having known the Father personally for some time or having been to St Raphael circles, etc.”

Years later, Fuenmayor would reflect on his memories.

With what great detail did the Father plan everything so that the workshop would prove fruitful! From the tiniest material details, to a whole host of practical hints he gave those with him at the time, on how to explain the more straightforward ascetical themes; for he himself had taken on the task of explaining the more delicate and important topics.

Two other Numeraries were with Amadeo de Fuenmayor: Odón Moles and Ignacio Orbegozo. Also present, at least for part of the time, were some of the older members of the Work: the priests Alvaro del Portillo, Pedro Casciaro (who gave one of the talks), and José Luis Múzquiz.

The founder received those who attended and was like their host in the house, which was still being set up. Some of the bedrooms had bunk beds and there were no sheets or blankets, so each had to bring their own.

How the workshop unfolded

St Josemaría’s preaching

The timetable included a meditation and a talk in the morning, a get together after lunch, a time for the “catechism” of the Work to get to know its particular Law and its spirit, and a time for prayer in the late afternoon. After a late afternoon snack there was another “catechism” session, the praying of the Rosary and a time for spiritual reading. After dinner and a get together, the day ended with a brief commentary on the Gospel and an examination of conscience.

On the day of arrival, in the evening, St Josemaría gave a preparatory talk in the oratory. De Fuenmayor noted down some ideas in the diary:

At the end, he tells them that on the following days he will not be talking to their hearts as he has done today, but coldly, because they are men of faith, and they should consider rationally the ultimate consequences of the truths he will set before them. The Father told them: 1) they have come here for divine reasons, as otherwise it would make no sense to have abandoned so many professional and family etc. concerns; 2) Those who give themselves to God in the world, in their profession and family, are also chosen by Him; it is a “divine vocation,” as the Pope says; 3) They have come to be with God during these days in order to grow in love for Him; 4) A path: the Blessed Virgin, Our Lady.

Those present kept silence only for the first day, following the pattern of a day of recollection; the other days were a workshop, combining means of Christian formation with free time, sports, get-togethers, etc.

Sunday, 26 September 1948

The day after their arrival, St Josemaría preached on the topic of vocation. He said “our mission on earth is to spread the kingdom of God; we have been chosen from all eternity for this purpose.” Alvira adds: “God has called me from all eternity.” Escrivá also emphasised that the awareness of this vocation should not lead to arrogance because “God has deigned to make use of his most wretched servants.” “How grateful I am for this calling!” writes Alvira. “So many clean and good souls, and yet he is calling me, a dirty rag.”

The founder went on to consider another topic, closely related to these reflections: divine filiation. “Always, a very special consideration that we are sons of God. As children, we should draw close to Him and love Him and return to Him after falls, and always count on his fatherly love, on his understanding. The Abba Pater of Jesus is the expression young children use to call upon their father: so that is how we call upon Him, with the security that He loves us exceedingly.”

“We should draw close to God as Father with the same naturalness, the same frankness that a child does with its father,” writes Alvira.

We know from the notes in the diary that Escrivá filled out the panorama he was trying to portray by talking about holiness in the middle of the world: “Draw close to God and get to know Him, scorning everything else. Honours and riches are mere means. To be happy here on earth and in heaven there is only one solution: being holy; and the holier one is, the happier one will be.”

The second meditation that day was on death: “He says he is going to do his prayer out loud,” wrote Fuenmayor. The founder’s preaching was direct, not beating around the bush: “how would my soul look to God if I died now? And what would I do about the things that worry me today if I knew I was about to die?” Among other things, Alvira noted down the following:

We all have to die. An old bishop told the Father that every month he meditated on himself becoming a corpse, imagining that they were giving him the last rites, that his arms and legs were losing warmth. And then he would think about what worried him, his projects, the people who didn’t like him, etc. A young workman without faith finally obtained divine grace. He became ill and died shortly afterwards. Addressing this young man, the Father said: I envy you, my son. But our soul enters God’s presence with only our good works, our sacrifices, our good intentions….

That day, St Josemaría held two sessions to explain aspects of the spirit of Opus Dei, including the norms and customs, and various human virtues. De Fuemayor wrote that these talks were very pleasant because they were “interspersed with numerous anecdotes and references to many aspects of the spirit of the Work, so that they could get to know it fully.”

The day finished with St Josemaría giving a meditation on faith, in which he commented on passages from Scripture:

The Father talked about how we need to be men of faith. Examples from the Gospel: (1) The blind man, when he knew Christ was passing by, dropped everything and went to find him. That’s how we should be: we should break energetically not our chains – fortunately there aren’t any – but the many silk threads that tie us down and stop us from giving ourselves to our Lord, asking him, like the blind man did, “ut videam”, that we might see those threads. (2) The man with the crippled hand. He too approaches Jesus asking him to cure him. And Christ in turn asks him to move his hand: that’s our cooperation, our action. And the hand is cured at our Lord’s word, restored. (3) The hunchback woman: she could only look at the mud and manure. So many are like that here on earth. But the mere presence of our Lord enables her to stand up straight and look at the sun and stars. We too need to look up. (4) The cursed fig tree. Our Lord, so human, was thirsty, and the fig tree appeared beautiful, with green leaves, sucking life from the earth, but it bore no fruit; and although it was not the season for figs, he curses it and it withers instantly, because we should always be producing fruit. (5) The apostles’ faith in the Guardian Angels. St Paul was freed from heavy chains, and when the servant went in to tell the apostles, who were all together, that Peter was at the door, they say “it must be his Angel.” The Work was founded on the feast of the Guardian Angels. They have been “accomplices” in all that has been done.

Monday, 27 September 1948

The next day St Josemaría preached a meditation on the kingdom of God. Taking military banners as his starting point, perhaps inspired by this traditional Ignatian theme, he referred to various attitudes regarding Christ’s loving lordship:

The Father, in the morning prayer, commented on the words of Jesus: “He who is not with me is against me.” There are two clearly defined fronts. The vision of a battle between three armies; one with black and red banners, enemies of Christ who continue to shout “Crucify him,” who are attacking Europe (Germany, Poland, Austria, Hungary); another of Catholics who are not really such, and who wave grey flags; and then true Christians, with a white flag and the Cross as their standard, who want to remedy the situation and bring about what Psalm II refers to, the “volumus regnare Christum.” It is frightening to look at the map of the world today; but the Redemption is also taking place today. The ever closer invasion of barbarians is horrifying. Women, innocent souls of children, property, all will be brutally trodden on, if Catholics do not learn how to be co-redeemers with Christ in their professional work, in their official positions and in the heart of their families.

Escrivá used this panorama to spur on his audience to take responsibility, reminding them that they were called to put Christ at the summit of all human activities; moreover, to be co-redeemers with Him in the midst of their professional, social, and family duties. He reminded them of his foundational experience on 7 August 1931: “And I understood that it would be the men and women of God who would lift up the Cross with the teachings of Christ at the summit of all human activities. And I saw our Lord triumph, drawing all things to Himself.”

The notes that Alvira compiled on this meditation are more explicit about the consequences of the absence of Catholics in public life: “The Redemption has not finished. Men are free to act; we have to act. Go to the highest places, to positions of influence, if we do not want to experience what has already happened in other countries: with women, with children, with property.” And he adds an anecdote from the preacher: “An old priest and a young priest meet, and the old priest asks: ‘how do you spend your time?’ The young one replies: ‘I get up late, I go to bed early, I don’t do much work…’ ‘That’s awful,’ the old priest tells him. That’s how you will be if you become bourgeois, if you don’t work, if you don’t take up posts of responsibility out of fear, afraid of tiring yourself out, or whatever.”

The second meditation was on the hidden life of Our Lord. He started by considering how Jesus came into the world: “without show, without noise or fuss.” Then he talked about “the thirty years of hidden life and only three of public life.” “The Work takes as its model the thirty years of hidden life. Contemplative life because God is in our hearts.” Alvira adds: “Active or contemplative life? Ours is contemplative. Our cell is the whole world. Christ in the centre of our soul. To conquer the world for Christ. Ours is a hard life, filled with sacrifice, and constant adoration.”

That afternoon, St Josemaría continued to talk about being instruments of God, who needs all kinds of tools. “So away with false humility (I’m no use, I can’t do it, etc.),” we read in the diary. “For a surgical operation, fine scalpels; to level the path, a steamroller,” he said, explaining how each thing has its use. And he concluded: “Away with cowardice. Look how Our Lord sought out the twelve apostles: in their professions, which some carried on with, even later on. Jesus calls you in the place where you are, in the work you are doing.”

That same day, Escrivá also took part in another session, on some points from the Decretum Laudis of 1947, explaining in detail various aspects of the spirit of Opus Dei. Two whole days had gone by and De Fuenmayor records: “The joy of each and every person there is immense, unbelievable.” And he cites the remark of one of those present, Pedro Zarandona: “I had never heard the Father talk before, and at the end of each of his talks I am moved. And the same happens to me at Mass.” The diarist wanted to make clear that he was not being carried away by enthusiasm: “Nothing I am writing is in the least bit exaggerated. It seems incredible but that’s the way it is. Our Lord is pampering us all with his grace. And what is happening this week is another example of his love for the Work, and his evident help in its labours.”

Tuesday, 28 September 1948

On Tuesday the 28th, St Josemaría gave three meditations. In the first one, he commented on the scene of the washing of the Apostles' feet during the Last Supper. “Jesus tries to wash Peter’s feet, but Peter doesn’t let him because of false humility. But then, when Our Lord says he cannot have anything to do with him, he reacts with his characteristic spirit: not only my feet but my hands and my head too. That is how our self-giving should be: total. It is true we are full of wretchedness, but Our Lord, with his grace, will help us with great power.”

He continued commenting on the passages about Christ’s Passion. “Jesus, from one tribunal to another, is silent. In contrast to this, so many wagging tongues – even from official Catholics – so much gossip. The terrible moment of the crowning of thorns. He buckles. It is my wretchedness that overwhelms him. Our lack of love. Finally, on the Cross, alone, nailed like an animal. His inner and outer senses feel the pain. Let’s seek him out to take him down from there and nail ourselves to the Cross.”

The second meditation was on mental prayer. The Father talked about topics to bring up in personal conversation with God and offered some bits of advice to pray well: “Worries, joys, desires, hopes, everything, talk about it with God. 15 minutes, and if possible 30. Leave out Communion rather then leaving out the prayer. In a quiet place: it could be a church, or often better at home. A divine and logical formula to start it with: My Lord and my God (St Thomas on putting his hand in Our Lord’s wound), I firmly believe that you are here, etc.”

He went on to speak about what the characteristics of prayer should be: “In the first place, prayer has to be humble: between the publican and the Pharisee, we must be like the former. Secondly, it should be simple, with the simplicity of children, from whom we can learn so much about prayer. Persevering: St Therese would make use of aspirations when she could do nothing else. Let’s be men of prayer, of interior life.

Alvira’s notes on this point reflect better the tenor of Escriva’s preaching:

Simplicity in prayer. A child that says: long live Jesus, long live Mary, long live my Aunty. A child that knocks at his father’s door with his hand, with his foot, with his whole body. And the father comes out with the idea of telling him off, but on seeing him, gives him a hug. That is how we should be in our prayer with Jesus. We should invoke Mary, Joseph and our Angel so that they come to our aid. We should never leave out the prayer from our day. A head of state has those on guard duty, and some consider it to be an honour while others spend their time thinking about their girlfriend. We should consider this time spent being on guard, in prayer, as an honour, and be there the exact time as planned, although during the half hour we may have looked at our watch forty times. If we have had the intention of praying, we will have gained a lot.

The final meditation that day was on mortification. As was his custom, St Josemaría commented on various biblical texts: “if a grain of wheat falls to the ground and doesn’t die, it fails to yield fruit; if it dies, it yields an abundant harvest. So we need mortification to be fruitful.”

He went on to talk about the self-conquests we need in order to be holy: “Small mortifications. Prayer of the flesh, of the senses. If an angel came down to tell us that holiness is possible without mortification, it would not be an angel of light, but of darkness.” He then mentioned St Paul, who spoke about his difficulties in overcoming his bodily weaknesses, and he used the metaphor of sports to explain the effort required in Christian life:

In sports people do so many things to win a prize. What about us? Run to win the trophy, says St Paul. Many take part but only one wins the prize. Mortification, a means to make the people around us happy (our great obligation). Our Lady knows a lot about mortification. Let’s try to take away one of the swords that pierced her heart so as to put it in our own.

That day the founder continued to explain the particular Law of Opus Dei; he focused on the “the obligations and privileges of Supernumerary members; the nature and scope of their bond with the Work.”

Wednesday, 29 September 1948

On Wednesday the 29th, St Josemaría continued speaking about the topics on Christian life that he habitually referred to in his preaching: charity, means to achieve holiness, little things, and spiritual direction. In the first meditation he commented on the Mandatum novum, explaining that the deeds of charity have to be done without drawing attention to oneself and without looking for human recognition. “The command is as new today as when Our Lord gave it, because nobody follows it. Christian charity, so forgotten by official Catholics. Instead of ostentatious almsgiving (foundations with the goal of preserving the memory of the founder), good works that nobody notices.”

Then he talked about a specific way of practising charity: living fraternity with those in Opus Dei. He asked that this manifestation of love be “true affection; the love of a brother, who praises him behind his back and corrects him face to face when necessary. The living example of Christ, who weeps for his friend Lazarus and who, moved by compassion, raises the widow’s son back to life. Charity without hypocrisy: with love and sacrifice.” Alvira’s notes, which become shorter as the days pass by, add: “Jesus did not say that his disciples would be known for their humility or purity, but rather for the love they have for one another. Careful with your tongue. There are people who go to communion every day but then cast aspersions on the good name of others.”

In the diary we read that the second meditation that day was on the means needed to achieve holiness:

Faced with a challenge, people tend to form three groups: foolish ones who cannot be bothered with the means (someone for example who wants to descend from the top of the post office tower without using the lift or the staircase); others who only use the means that they personally like, that are agreeable to their will; and finally those, who because they feel sick, do not reject any medicine. Moreover, this last attitude is a logical consequence of our self-giving. If we are to serve faithfully, we must make use of the only effective means available: prayer, mortification and work. Not to do so would be a form of cowardice that would weigh on us our whole life. Our Lady, to whom we should ask for help, makes these means pleasant and sweet for us. A general, wide-ranging resolution: Love. Moreover, small and specific daily resolutions.

In the evening, the founder talked about the importance of little things, particularly in what refers to the plan of spiritual life, that is, the acts of piety that mark out the day for a member of Opus Dei:

Fulfilment of the plan of life, faithfulness in small things. Our Lord says about the widow who puts a few small coins in the basket: I assure you she has put in more than anyone else. Perseverance, with humility, placing ourselves in our Mother’s arms like children so that she picks us up and carries us. Holiness involves the careful fulfilment of our obligations, because saints are made of flesh and blood, not cardboard. The example of Isidoro (Zorzano); he attained holiness in ordinary work, with extraordinary humility.

In the last meditation that day he considered “the weekly chat and the direction that the Work offers its members through the directors and priests;” in other words, everything required to make fruitful use of the spiritual accompaniment that the faithful of Opus Dei benefit from on their path to holiness.

Thursday, 30 September 1948

The last meditations given by Josemaría were on Thursday the 30th. In the first one, he commented on the parable of the good seed and the thorns: “The good sower, who sows wheat. Then the enemies come and sow tares in a cowardly way. That’s the way things are on earth! How many sow weeds ! They are cowards, because then they run away. And all because those, to whom the Lord had entrusted the field, did not look after it. Let’s not be homines dormientes, men who are asleep.”

He said that we need to be vigilant like this in our personal life, to detect subtle temptations from the devil: “He won´t come to us crudely offering us a piece of raw meat, but well prepared, seasoned, and in little things: we have to be strong. We already know what the means are: prayer, mortification and work. Don’t be afraid of penance; this is something you should talk to your director about.” Taking this parable further, he went on to talk about how members of Opus Dei should try to be a Christian influence in the places where they live and work. He explained the characteristics that personal apostolate should have in professional environments: “Prestige in the work place; hold your head up high in front of your colleagues, with humility; and give them criteria without ‘preaching’ to them (we aren’t Dominicans). And moreover, acquiring a new sense of everything, which fills us with peace and joy.”

In the evening that same day, he reflected on the history of the Work, and specifically on the persecutions it had suffered, sometimes from within ecclesiastical circles. Now, after its approval as an institution of pontifical law, the Church had blessed it and put it forward as an example. He finished by saying that this also happens in people’s lives as well: “illnesses, bereavements, setbacks, economic difficulties, professional betrayals, trials... and then the sun shines.” Referring to Jesus and the miraculous catch of fish, in relation to the vocation to Opus Dei, he pointed out:

You shouldn’t think that this dedication will harm your family life or economic interests in any way at all. When Peter was doing everything he could to fish but without success, Jesus showed him the right place and he brought in an abundant catch of fish without breaking the nets.

Although our work in the world will increase, our nets (work, home, etc.) will not break.

Their time there was coming to an end and St Josemaría used the last meditation to talk about perseverance. He wanted to give it late in the evening so that the next day they could leave early. Among other things, he told them:

Many begin but few reach the summit. In our case, few begin but I am sure many will finish. God’s grace will not fail us. In the Acts of the Apostles, we read that the first Christians were persevering in prayer, the word and the breaking of bread. Stubbornness. Let’s be obstinate in this matter, and if one door closes, another will open. From now on, let us be children of our good and fair mother, the Work, “cor unum at anima una.”

The days in Molinoviejo as seen by those present

We have already cited impressions of Amadeo de Fuenmayor, the person who kept the diary, regarding the joyful satisfaction that took hold of those present, as the founder revealed before their eyes the panorama of giving oneself to God as Supernumeraries. We will now look at some of their impressions regarding different aspects of the workshop, which many of them would never forget.

The family atmosphere and St Josemaría’s preaching

One of the formation challenges in this new stage in the history of the Work was to transmit to the Supernumeraries the spirit of filiation and fraternity that are characteristic of the Work, and that the founder considered to be essential. Until that time, there had only been Numerary members, who had already absorbed these aspects, to a greater or lesser extent. It remained to be seen how those who spent less time with one another and who would see the founder less often, would incorporate these spiritual features into their lives.

One can understand therefore the satisfaction that shines out in a note written by Fuenmayor: “I cannot fail to record the fact that the three who have met the Father this week – Hermenegildo (Altozano), Juan C. (Caldés), and Pedro (Zarandona) – have independently and spontaneously commented on the great affection they feel towards him. It’s marvellous to see how deeply this spirit of filiation has taken hold in them.” He notes elsewhere: “It’s wonderful to see how those who did not know each other three days ago, now treat one another as old friends, like true brothers who love one another dearly. They themselves notice it and say how wonderful it is.”

This atmosphere was due above all to the presence and example of the founder. Years later Alvira reminisced:

The Father was attentive to everyone and encouraged us, with the good humour that was habitual in him. Everything the Father said sunk in deeply and a great spirit of friendship arose. So now, after many years, this true friendship reminds us, when we see one another, of those days we spent with the Father, receiving doctrine and seeing new paths for our spiritual life that have done us so much good.

Juan Caldés remembered him as “always overflowing with joy, readily breaking into a smile and sometimes a hearty burst of laughter.” In their free time they played soccer or went for a swim in the pool, sang or listened to music, and in the get-togethers after lunch and dinner they shared personal stories and memories. “Everyone talked as though in a family whose members loved one another dearly,” Ivars recalled . “I didn´t know most of them until then but it seemed like I had been living with them for ever. The get-together was like a good party.”

Juan Caldés remembered the founder clearly:

From the moment he received us (in the sitting room by the oratory) with friendly words (“this is your home; welcome; it’s poor but it’s made of love”), I felt a strong attraction to something special. Later, as the course continued, that attraction grew stronger because in each Mass, in each meditation, you felt as though God’s grace was flowing from him and pouring out in his words.

This impression was no exception. Years later, others who were there recalled St Josemaría’s preaching: “He would normally comment on a passage from the Gospel,” remarks Antonio Ivars. “It was impossible to get the least bit distracted. He seemed to be speaking directly to each one. He spoke in the singular, and often said ‘you and I,’ rather than addressing the group as a whole.”

The panorama of the vocation

St Josemaría counted on the experience of the weeks of formation that the Numeraries had already been doing for years. But this workshop required quite a few tweaks and a comprehensive grasp of the characteristics of a Supernumerary that only the founder could have. Judging by the testimonies of those there, the message was received loud and clear. For example, Ángel Santos kept notes of the ideas he heard during that week. Reading them today, they can be a good summary of the essential features of a Supernumerary:

Sanctifying our ordinary work, seeking the fullness of Christian life. Sanctifying the world from within through our interior life and the fulfilment of the ordinary duties of a Christian; being contemplatives, with naturalness, in the midst of our daily tasks; carrying out an apostolate of friendship and confidence that encompasses our whole existence and that raises friendship to the heights of charity; being sowers of peace and turning where we live into bright and cheerful homes. And all this with strictly individual responsibility – without ambitions to represent anyone, without any clerical tendencies – characteristic of a mature laity. Far from a religious vocation but at the service of the Church. For this we would count on, going forward, a suitable doctrinal formation, spiritual direction, the warmth of our brothers and encouragement for personal initiatives.

For some, this panorama was a novelty. They had all known, for a greater or lesser amount of time, the founder's ideas, even those who had not known him personally, but perhaps none of them had until then such a complete and clear vision of what the life of a Supernumerary involved.

As we have said, those present had lived their faith intensely for years and several had been active in lay apostolates. Nevertheless, what Mariano Navarro Rubio wrote about those days in Molinoviejo is significant:

My usual way of thinking, forged from an early age in Catholic Action, was exposed to these ideas, which seemed aggressive novelties to me given the way I had of understanding religion up till then. The Father talked constantly about sanctifying ordinary work, with an insistence that undoubtedly pointed to a key idea; about the apostolate “ad fidem” – about friendship with Protestants and Jews – which seemed a bit strange at that time; about a smiling asceticism together with that other wonderful idea of contemplative life in the middle of the world. All this sounded like a religious renaissance, like a living glory. At a single stroke, one saw everything the same as before, but with a different colour. A vision was created, both demanding and optimistic, that spoke about the vocation to holiness of lay people, whereas everywhere else we were considered as second-class Catholics. Married life especially was seen, in the light of faith, with a new richness, unknown to me and I think to all the others until then.

Saying yes to one’s vocation

According to the testimonies that we have, they all saw clearly that Opus Dei was not an association based on temporary circumstances. From the founder’s explanations they understood very well that it was something quite different. Antonio Ivars wrote:

The Work was very young and it was growing rapidly. The phrase “the waters will pass through” was written on a plaque in the pantry, and a little fountain in one of the corridors bore the words “inter medium montium pertransibunt aquae,” the waters will pass right through the mountains.The Work aspired to be an intravenous injection in the bloodstream of society. The whole key was in the “unum neccesarium”: personal holiness, each in his own place and job, striving for perfection, for the glory of God, forgetting about oneself, and without making noise.

Juan Caldés wrote down Escrivá´s words: “‘You will see wonderful things.’ But always, always as a ‘gift from God,’ as a proof of his loving providence.” “Through his commentaries,” recalled Carlos Verdú, “he spoke to us with great faith about events and the future development of the Work. The Father spoke about these things with such assurance that he gave the impression he already saw them all made a reality.”

“That week,” Ivars adds, “was decisive for everyone. It was all clear and simple. Moreover it was logical and sensible. We would continue being the same, doing the same things, but always aiming towards a goal: personal holiness. We heard these light-filled words: ‘Your life will be a beautiful novel of love and adventure.’ And years later, many years later, we have seen it all come true.”

Ángel Santos remembers that during the last days “the Father took a stroll with each of us individually, along the little stream that ran through the property. My conversation was mainly one of expressing gratitude for the marvellous gift he was giving me, to be able to belong to the Work and dedicate my life to God, within my civil state as a citizen and ordinary Christian.”

Manuel Pérez Sánchez also remembers a conversation in which St Josemaría said to him, among other things: “with complete freedom let me know your dispositions; I am not coercing you in the least. If you are not ready, tell me frankly; don't do it for me. Whether or not you are willing to be a Supernumerary, I’ll always love you just the same.” Silverio Palfox, the doctor from Valencia, remembered his chat with the founder:

He took me firmly but gently by the arm. I was literally astonished by the things he knew, not only about myself, but also about “quite unusual” things that interested me a lot and that most people knew nothing about, or misunderstood or feared even to look into: the first origins of life, evolution, biological foundations of sexuality and thought, hygiene, nature-based medicine, etc.

Two things stayed strongly in my memory: one: “Thank God for this vocation that he has given you as a reward for helping your brother follow his own one.” And another: “It gives me a lot of joy that with great piety, prudence and formation, you are illuminating with doctrine all these topics that are in the hands of Marxists, masons, materialists....” And he gave a humorous example: “Because it will also give me great joy when I have a bullfighter son; but I can't tell someone to become a bullfighter just so I can boast that there are bullfighters in the Work. Each has to do what he wants.”

Pedro Zarandona also remembered clearly “strolling along the little stream that ran across the property, close to the old pine grove. In a natural and intimate conversation, he took me by the arm from time to time as a gesture of confidence, and he talked to me with words filled with faith and love for God about the marvellous vocation of giving oneself in the middle of the world, sanctifying work and the ordinary things of each day. Those words confirmed me in the decision I had taken a few months previously to ask to join the Work.”

The diary from those days finishes like this: “The week has come to an end, and it stays firmly in our minds like a dream, a true dream. Our Lord has made known to us new horizons that fill us with joy and happiness. And they will return to their homes and their work to continue with their same lives, but with a clear purpose, divine dreams and a vocation to holiness.”

Conclusions

In light of the documents and testimonies that we have looked at, we can draw some conclusions. First, the founder succeeded in transmitting to the attendees the fundamental idea of what a Supernumerary in Opus Dei was: that it was a vocation to attain holiness in the world. To say this in 1948 was surprising, even to those who had known St Josemaría previously and who were familiar with the spirit of the Work. Everyone knew that the marital state was not incompatible with a deep Christian life, but to consider it in terms of vocation, with all that this term implied then and now, was something new.

This discovery produced great joy and surprise in the group there. They were people who wanted to give themselves to God and several of them had tried to do so or had considered it before, thinking about becoming priests or Numeraries, only to realise that it was not for them. Now, at last, they found their vocational path.

From what we know, his message to that group of men, married or planning to form a family, did not differ from what he had been saying to groups of men and women who wished to live this vocation in celibacy. The primacy of the contemplative life, the sanctification of work and the realities in the world, the responsible participation in temporal challenges, serving God and society from one’s own place, with a desire to radiate as much as possible a Christian spirit, without being afraid to occupy important or prestigious posts if God called them to do so, are themes that he always preached on. Thus, to put it in some way, he didn’t have a specific message just for the Supernumeraries.

The biographies of the attendees, as can be seen in the appendix, show us a group that was mixed in terms of backgrounds, places of origin and prior knowledge of the Work. At the same time, we can see some common features: they all had a university education or, in the case of two of them, were officers in the Navy. They were all professionals, and several had even managed to become high profile people in the scientific, political, cultural or economic circles of Spain. Also some of them would develop a concern to get involved in social initiatives. As far as their political leanings or affiliations were concerned, the documents we have seen don’t say anything about this, due in no small part to the fact that the Work avoids asking people for their opinions on these matters, in order to respect their freedom. We know that some of them, for example Fontán, were very close to Francisco Franco, and that Navarro Rubio would become a minister in the regime, although he is normally viewed as a Catholic “technocrat,” and that Altozano was a monarchist. We can assume the rest held more or less the ideas that were common among Spanish Catholics of that time, who had lived through the Civil War and who had supported the Nationalist side.

Twenty years had passed since the 2nd of October 1928, and the founder had been able to think through, in the light of the foundational charism and his own experiences over these years, a practically definitive vision of the Supernumeraries, which was largely what he transmitted to them during those days and which would be set down in writing, a few months later, in the Instruction for the Work of San Gabriel. From that time on, this part of the Work would start developing in a definitive way: of the 2404 men members and 550 women members in Opus Dei at the beginning of 1950, there were 519 men Supernumeraries and 163 women Supernumeraries.

Appendix. Brief biographical information about those attending

(in alphabetical order)

To compile these brief biographical notes, we have used documentation available in the Prelature’s General Archives. This includes testimonies written by several of the protagonists for the cause of canonization of St Josemaría, as well as brief unsigned obituaries written on the death of the people themselves. Given the aim and limits of this article, we have not searched for other primary information in public or private archives, but have used only information in the public domain, which can be found in various publications and web pages.

Hemenegildo Altozano (1916-1981)

He was born in Baños de la Encina (Jaén) on 23 December 1916. In 1931, he started a Law degree when he was only 15, at the University of Granada. In the years of the Second Spanish Republic, he was president of the Association of Catholic Students of Law and Philosophy in his university. When he completed his degree, still very young, he obtained a job in the juridical branch of the Army. He took possession of this job when the Spanish Civil War ended. Later he taught in the Naval Academy in Marin. In the Navy he achieved the grade of Auditor General.

From 1949 to 1955 he was secretary general of the government in the territories of the Spanish colony that is now the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, during very difficult times. As Antonio Fontán wrote, Altozano “was both a lawyer and a prestigious army man, as well as an independent and unconventional politician.” He supported the monarchy and formed part of the council of the Count of Barcelona. Between 1959 and 1962 he was civil governor of Seville. When he retired from politics, he was director of the Banco Hipotecario de España. He was known as a “deeply human person, who earned the respect and sympathy of everyone in the various public functions he carried out.”

He met St Josemaría in Molinoviejo, at the workshop described in this article. Those who knew him in Opus Dei describe him as a kind and refined man, smiling and balanced, with many friends who he tried to bring closer to God. He and his wife had eight children.

He died from cancer in Jerez de la Frontera (Cadiz) on 12 September 1981.

Tomás Alvira (1906-1992)

He was born in Villanueva de Gallego (Saragossa) on 17 January 1906. Some biographies of his life are already available. He studied Chemistry at the University of Saragossa. His professional life was spent mostly teaching in secondary schools. He worked in several schools, in some of them as Headmaster. At the end of the Spanish Civil War he started teaching at the Instituto Ramiro de Maeztu in Madrid, where he secured a permanent position in 1941. The “Ramiro” as it is known in Madrid, was a centre known for its excellence, where Alvira was part of a prestigious faculty.

He was also head teacher at the Colegio de Huerfanos of the Civil Guard. He took part in the creation of Fomento de Centros de Enseñanza, a foundation that has set up many schools in Spain inspired by Christian principles, which started in 1963. Victor Garcia Hoz and Angel Santos were also involved in this effort. From 1973 to 1976 he was assistant director of the Experimental Centre of the Institute of Education at the University of Madrid, and later director of the University School of Fomento de Centros de Enseñanza.

His first contact with the founder of Opus Dei was in Madrid, in the middle of the Spanish Civil War, on 31 August 1937. A few days later, Alvira received a surprising invitation in those circumstances: to attend a three-day long spiritual retreat, preached by the founder of Opus Dei, with four other people. Because of the religious persecution then underway, a great risk was involved in taking part, and they had to meet in different houses to have the various meditations, so as not to raise suspicions. When St Josemaría decided to escape to the nationalist zone in order to carry out his priestly ministry in freedom, Alvira joined the group of fugitives.

Alvira married Francisca Dominguez (Paquita) soon after the end of the war, in June 1939. He continued to be in contact with St Josemaría in the years that followed. In 1948 he asked to be admitted in Opus Dei as a Supernumerary. His wife also became one of the first women Supernumeraries. They had nine children.

He died on 7 May 1992. The process of beatification for him and his wife has been opened.

Emiliano Amann (1919-1980)

He was born in Bilbao in 1919. He was the son of a well-known architect, Calixto Amann (1882 to 1942). When he finished school at the young age of 15, he went to Madrid to prepare for entry into Architecture school and he found lodging in DYA, a residence that had been set up in 1934 as an initiative of the founder of Opus Dei. The letters that he wrote to his parents from the residence, and which have been published in this magazine, reflect the daily life of the first members of the work and of its founder, who carried out a wide range of activities of Christian formation.

For a time, due to the outbreak of the civil war, he was not able to continue to receive the formation and spiritual guidance in DYA, but when Josemaría managed to escape from the religious persecution and set himself up in Burgos, he contacted him again and experienced his fatherly concern, both in person and by letter. One of Amann’s letters is the basis for points 106 and 977 of The Way.

When the war came to an end, Amann went back to Madrid where he helped to set up the new residence in Jenner Street, where he would live. From there he moved to the residence, Moncloa, that had started its activities in 1943. He continued to see St Josemaría but less often than before. On finishing his Architecture degree in 1946 he returned to Bilbao. Of course, Escrivá had already talked with him about a "vocation to marriage" and St Josemaría officiated at his marriage to Carmen Garamendi, in Algorta (Vizcaya, in the Basque Country) in 1948. When he explained to him in Molinoviejo about the possibility of becoming a Supernumerary, Emiliano recalls “I did not doubt for an instant because I trusted the Father.”

As an architect in those developmental years, Emiliano carried on his father's line of work, which was to design social housing that would reduce costs and make better use of space. He also worked as a diocesan architect between 1956 and 1960, completing various projects for Viviendas de Vizcaya, for Obra Sindical del Hogar, for the Banco Popular and for Telefónica. In addition, he was also involved in buildings that would be used for apostolic activities related to Opus Dei, like the retreat house Isalabe.

He died on December 13, 1980.

Juan Caldés (1921-2008)

He was born in Lluchmayor (Mallorca) on January 1, 1921. The family had to move to Madrid, where Juan went to secondary school, obtaining an official prize from the state for his outstanding performance in public examinations.

After the civil war he read Law at Salamanca, finishing his degree in 1944. A year later he obtained a doctorate in Madrid and successfully applied for the post of Legal Officer in the Social Institute of the Navy in 1946. That same year, he founded in Madrid the University Academy, San Raimundo de Peñafort, aimed at workers from various sectors, so that they could study for a law degree in the evenings. The academy came to be a model center of its kind and it inspired the creation of other similar centers in Spain. By 1956 hundreds of workers had finished their law degree.

Together with Leonardo Prieto Castro, university professor of procedural law, he also founded the School of Legal Practice in Madrid University. Almost fifty years later, there would be seventy-four schools of this kind in Spain.

During his studies in Valencia, he had got in contact with the Work thanks to Amadeo de Fuenmayor and José Montañés. He asked to join as a Supernumerary on July 15, 1948, a few weeks before going to Molinoviejo. When Josemaría talked to him, he did not have to raise the idea of a possible vocation, as he did with others: “as he took me by the arm and walked,” recalled Juan, “he just made one, very specific recommendation: next year he wanted to see me there with two friends. His apostolic desire was without measure.”

He married Consuelo Llopis, also a Supernumerary. They had ten children.

Throughout his professional career he held various positions of responsibility related to economics and law: in the General Council of Lawyers, the Spanish Law Society, the Confederation of Organizations for Social Provision in Spain, etc. From 1958 he also worked in banking, first in the Banco Popular and then as director of the Institute of Credit of the Building Societies (Cajas de Ahorro), where he remembered spending his four happiest professional years. Traditionally the building societies supported social and cultural works, and Caldés promoted this with the creation of homes for older people, schools etc. In 1972 the Credit Institute was absorbed by the Bank of Spain, where Caldés became the General Director, a post he would hold until 1984. After that he returned to law practice.

He died on May 30, 2008.

Jesús Fontán (1901-1980)

He was born on April 26, 1901, in Vilagarcía de Arousa (Galicia, in the north west of Spain). He was in the Navy, where he reached the rank of Vice Admiral. As a boy living in Ferrol, he met a friend of his brother’s. His brother’s name was John. His brother’s friend was older than he was. This friend used to come and study at their home; his name was Francisco Franco. They became close friends and this was the reason that the Spanish dictator and General named him as his assistant, in February 1939.

Fontán started navy school in 1917 and later obtained the qualifications of airship pilot and of naval observer, as well as the diploma of Military Staff Officer. During the civil war he was arrested in Madrid in September 1936, and spent two months in the Modelo prison. On release he went over to the nationalist zone in June, 1937. He was then posted to several ships and worked in the General Army Barracks in Salamanca.

In 1942 he met José María González Barredo, one of the first members of Opus Dei, a professor at the University of Zaragoza, who talked to him about St Josemaría. The next day Jesús and St Josemaría were introduced. Jesús was bowled over by St Josemaría’s kindness. At later meetings, Jesús witnessed the confidence with which the founder talked about the future development of the Work. During those years Jesús Fontán also had contact with Álvaro del Portillo.

At the beginning of April 1946, he stood down from his position as Franco’s assistant to take charge of the vessel Galatea. In the summer of 1947, he received the pleasant surprise visit of St Josemaría and Álvaro del Portillo in his home in Pontedeume. With his wife, Blanca Suances, also a Supernumerary, they had six daughters and two sons. Jesús recalls: “with the affection that the Father always put into everything, he looked at my children and said 'I need to have one or two of these' and the Lord granted him the vocations of two of them… As he was leaving he said to me 'You can be in the Work now'.”

After holding positions of great responsibility, he resigned from the Navy in 1967, but not from his contact with the sea. That year he was appointed president of the Instituto Social de la Marina, an organization that offers health assistance and social provision for those who work at sea, as well as other types of help for people in this tough line of work and their families. He stood down from this post in 1976 at the age of 75.

He died August 26, 1980, at his home in Cabañas (La Coruña, also in Galicia). Many of his navy colleagues, whom he had tried to bring closer to God during his life as a Supernumerary, were present at his funeral.

Rafael Galbe (1919-2012)

He was born in Zaragoza in 1919. There he read Law at university. In 1937, during the civil war, sailing on the cruise liner Canarias, he reached Mallorca, where he met José Orlandis, with whom he would always maintain a close friendship. He was Lieutenant Auditor of the Reserve List of the Judicial Corps of the Navy.

His came in contact with Opus Dei in Zaragoza, during regular trips that members of Opus Dei made to that city. In the academic year 1942-43 he moved to Madrid, to prepare for examinations for entry into the judiciary. There he used to visit Saint Josemaría and José Luis Múzquiz at the house on Lagasca Street.

Galbe began his career in the judiciary in 1947 and was sent to work at the local law court in Jaca. In 1948 San Josemaría thought that he could be a Supernumerary. Rafael was excited by this idea, as were the others on that workshop. Later he became a Numerary. In 1949 he was posted by the Spanish government to what was then known as the Gulf of Guinea.

In this Spanish colony he was known for his apostolic activity with the younger Europeans, who found it hard to live a Christian life in that environment, morally looser than Spain at the time. In April 1953, he was appointed judge in the first hearing and appeal courts of Santa Isabel and president of the colonial court and high indigenous court. In May 1960, he was promoted to magistrate, continuing as head of the Justice Services of Guinea, as it was then called.

In 1966 he was president of the Equatorial Guinean Law Courts. On October 9, 1968, he stepped down from the post of Deputy General Commissioner of Equatorial Guinea, the day on which Spain granted independence to the new country. Those who had dealings with him there knew him as an honest man of great faith, with high moral principles and a strong character.

In the mid-fifties he formally left Opus Dei; he always maintained a reputation as a believer, a thoughtful person and above all, as a man of service. He remained single his entire life.

After returning to Spain, he became president of the court of administrative disputes in Zaragoza. He died in Zaragoza in 2012.

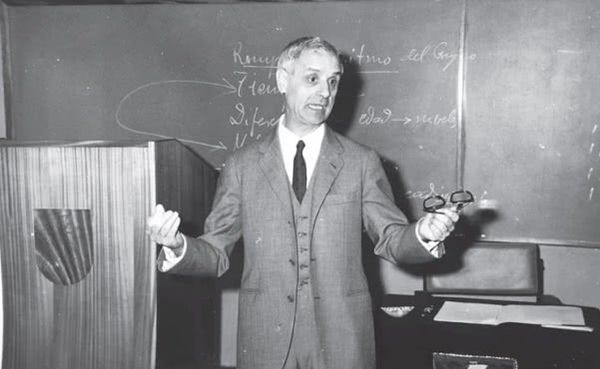

Victor García Hoz (1911-1998)

He was born in Campillo de Aranda (Burgos) in 1911. In 1940 he obtained a doctorate in Pedagogy and in 1944 he became a professor of experimental and differentiational pedagogy in the faculty of Philosophy and Arts at Madrid University.

He married in August 1939, shortly after then end of the civil war. Together with his wife, Nieves Rosales y Laso de la Vega, he was looking for a spiritual director when he met the founder of Opus Dei. Casimiro Morcillo, the Vicar General of the diocese of Madrid, was the person who put them in touch. They saw each other regularly until 1946. From these talks of spiritual direction, Víctor remembered a sentence that at the time "astonished him": “God calls you to paths of contemplation.” In those years it was not easily understood that you could say this to a married man, with a daughter and expecting more children (which in fact came), working to support his family, as though it was something he had to practice. He and his wife, who would also become a Supernumerary, had eight children.

Around 1942 St Josemaría talked to him about the possibility of responding to “a special, divine vocation to seek holiness in the middle of the world. He suggested that I, together with another person, Tomás Alvira, began to live the customs and norms of the Work without formally belonging to it. I was overjoyed by this idea. With a patience that never ceased to amaze me, St Josemaría gave a circle to Supernumeraries, even though they did not really exist yet, which Tomás and I attended."

The academic and professional biography of Víctor is very broad. He was director of the Institute of Pedagogy of the High Council of Scientific Research, until 1981; a permanent member of the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, and of scientific societies; pedagogical consultant – commissioned by Unesco – for various countries. He obtained several honorary doctorates, and numerous national and international prizes. With hundreds of publications, perhaps his most important work is the monumental treatise on personalised education, in thirty-three volumes, with the collaboration of European and American teachers, that he finished in 1997 at the age of 86. Up to just a few days before his death, he would arrive punctually for work at Fomento Centros de Enseñanza, the company behind many schools with a Christian grounding, in whose creation and promotion Tomás Alvira and Ángel Santos enthusiastically participated.

He died in Madrid on February 18, 1998.

Antonio Ivars (1918-1997)

He was born in Valencia in 1918. He read law in his hometown and did his doctorate in Madrid. His knowledge of St Josemaría went back to the first trips of St Josemaría’s to Valencia, after the Spanish Civil War, in 1939. He remembers that a close friend spoke about him: “He described him to me as a holy priest, dedicated to the formation of youth. He talked to me about some circles that took place in a modest mezzanine at number 9, Samaniego Street, which he invited me to attend.” There he met St Josemaría on a day when the founder was “lying down on a small bed with a fever, ill and thin.” Once he felt better, he heard his confession and invited him to attend his Mass, which had a profound effect on him. As a result of this meeting he remembers “My life changed. I had been anxious over the last years to find something that would fill my life completely and this was just what I had been looking for without realising it.”

In 1940, when a university residence in the same Samaniego Street was in operation, Antonio Ivars had a conversation with Pedro Casciaro and Amadeo de Fuenmayor. They told him that St Josemaría had mentioned that he had a “vocation to marriage” and that “they should not worry him.” From those first contacts with Opus Dei, he already felt part of the Work: “I was a Supernumerary, but I was not one officially until ten years later. Nevertheless, my vocation arose from that first moment.”

Professionally he worked for the Tram and Railway Company of Valencia as General Secretary. In 1957, motivated by his concern for the improvement of the professional world, he founded a school for the formation of top executives, a pioneering initiative in Valencia. He wrote various books related to the formation of managers and to company management.

He organised discussion groups with people as a way of broadening his circle of friends. A good number of Supernumeraries from Valencia say they are sure that they discovered their vocation thanks to him. In 1982 he founded the Escuela Tertulia (discussion group school), where small groups of businessmen would go every week to talk about professional, social, cultural and humanistic topics.

In the last stage of his life he suffered from Alzheimer for ten years. He died on April 25, 1997.

Mariano Navarro Rubio (1913-2001)

He was born in Burbáguena (Teruel) on November 14, 1913. He spent his childhood and early youth in Daroca (Zaragoza). He studied Law in the University of Zaragoza. As a republican in his thinking, and opposed as much to the left-wing parties as to those on the right, he found in Catholic Action a good place for his activity. When the Spanish Civil War came to an end, he graduated from the army as Provisional Captain of the Regulars.

He prepared for a doctorate in law and joined the Academy of the Military Judicial Corps. He was living in Madrid and was a member of the High Council of the young men in Catholic Action, when in May or June 1940 he met St Josemaría, thanks to Alberto Ullastres, president of the Diocesan Council of Madrid and a colleague of his, also doing a doctorate in law.

Navarro was in the process of looking for a spiritual director that would resolve his doubts about a possible vocation to the priesthood. To begin with, St Josemaría encouraged him in that direction, but a few days later he advised him to wait and to think whether God was not calling him to marriage. A series of events over the following days made him see that the founder of the Work was right. He married María Dolores Serrés Sena, with whom he had eleven children.

Something similar happened in relation to his professional career. While respecting his freedom, St Josemaría suggested that he could consider going into politics, instead of trying to gain the professorship in Law that Navarro aspired to. Initially disconcerted by this unexpected advice, reality showed his qualities were suited to politics, as Escrivá had intuitively guessed. Indeed, as Navarro himself remembers, “In 1947 I was named Court Attorney. In 1955 I was named Undersecretary of Public Works. In 1957 Minister of Finance and in 1965 Governor of the Bank of Spain. There is no doubt the Father was right.”

Navarro continued to talk with St Josemaría, as his affection for the Work grew. In 1947, while he was in Rome, he had an interview with St Josemaría, together with Víctor García Hoz. St Josemaría told him that the moment had arrived in which married people could now join the Work as Supernumeraries. When they asked him if he wanted to be one, he replied resolutely that he did. St Josemaría told him to ask García Hoz to teach him the Preces, and that day they prayed the Preces together in the hotel.

As we have seen, Mariano Navarro Rubio held important posts in Spanish public life. He won a lot of recognition and awards for his work; he was also a scholar in economics and politics, and an academic in the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences. He was one of the main promoters of the National Plan for Economic Stability which modernised the Spanish economy and administration, leading to large economic growth during the years when he was Minister of Finance. His brilliant career was cut short in 1970, while he was Governor of the Bank of Spain, when he was accused in the so called “Matesa Case.”

Illness caused him to be housebound in his final years. He died on November 3, 2001.

Silverio Palafox (1921-2015)

He was born in Granada in 1921. When he was studying Medicine in Valencia, he started to frequent the residence in Samaniego Street, encouraged to do so by Father Eladio España, a priest and a good friend of St Josemaría. In 1940 he met the founder in Valencia. Pedro Casciaro invited him to give Biology classes in the residence to those who were preparing for public exams. In 1942 he was doing a retreat in Madrid, which St Josemaría was giving, when he joined Opus Dei, but he lost contact straightaway as he volunteered for the Blue Division, a group of young Spanish men who fought in Russia. He retuned a year and a half later, disappointed by what he had experienced and transferred his academic studies to Salamanca University.

He maintained sporadic contact with Opus Dei and St Josemaría until one day, following a suggestion from his bother Emilio, he asked Pedro Casciaro “what is all this about ‘supernumeraries’.” Casciaro showed surprise but he replied with a smile: “Nothing yet, but there will be. Keep striving to be good and pray about it.” After a time, they invited him to go to Molinoviejo, to the workshop we’ve been talking about, where he found out what he had wanted to know, and he became a member of the Work. In 1950 he married María Dolores Bogdanovitch. They had five children and from the very start they had wanted to create a Christian home for their family. He was an active scientist, exponent of the neo-Hippocratic current of natural Spanish medicine. He obtained doctorates in hydrology, psychiatry, endocrinology, and in the history of medicine, supervised by prestigious academics. He taught various courses at the Complutense University in Madrid. In 1947 he created Binomial Notebooks, a magazine that aimed to promote the study of natural medicine, hygiene, diet, vegetarianism, natural healing methods and the tendency of organisms to cure themselves, in a context of humanistic medicine. He was academic in residence of the Royal National Academy of Medicine (1980) and founder of the Spanish Association of Doctors of Natural Medicine (1981), and its president until 1997. He died on March 23, 2015, at the age of 93.

Manuel Pérez Sánchez (1905-2002)

He was born in Herrera de Ibio (Cantabria) on November 8, 1905. After secondary school in Santander, he moved to Madrid in 1924 to prepare for entry into university to study Civil Engineering. There, his friend Manuel Sainz de los Terreros, also from Cantabria, invited him to some activities of Christian formation that the founder of Opus Dei was organising.

He met St Josemaría on March 18, 1934, during a retreat in a residence in Manuel Silvela Street that belonged to the Redemptorists. A little later he asked to join Opus Dei. For some years he had been helping out in activities that the St Vincent de Paul Society organised in the parish of St Ramón, in the area of Puente de Vallecas in Madrid. One of those taking part in these activities was a first-year Civil Engineering student, Álvaro del Portillo. One day, when everyone was animatedly talking about Josemaría Escrivá, Pérez Sánchez decided to introduce him to Del Portillo, and this took place a few days later in the DYA residence. Blessed Álvaro was forever especially grateful to Manuel Pérez Sánchez for having introduced him to St Josemaría.

The Civil War took him by surprise in Santander. When St Josemaría was able to get to Burgos, they made contact again. From time to time, Pérez Sánchez was able to make a very necessary loan to help the founder and those with him get over some financial difficulties.