I am a photojournalist, seeking a story behind every photo, the person behind the story and hope behind the life. My aim is to try to portray in photographs the human condition in Brazil, Spain, Kenya….

For 80% of humanity, life is a lottery where God seems to have split the tickets between the same winners. Faced with this scenario, my question is quite simple: what would have happened if I (a native of Andalucía) had been born fifteen kilometers below the strait of Gibraltar, in a different culture and religion? How and to what extent does a country and family influence us?

“I build my life with the biography of the others,” says well known photographer Richard Avedon. So I seek the humanity in the persons I portray. In the first place people, then ideas.

My job is simple. I try to tell stories with photos just like any photojournalist. Professionally, I work in corporate communications. For example, I transform into images the corporate identity of educational, social or economic entities, whether universities, NGOs, or business schools.

Photography is both memory and identity, and I try to look for these two aspects in documenting people and institutions that wish to improve their public communication. It is not about just taking pictures, but about truly reflecting people and entities according to their specific characteristics: sometimes, the images of people’s stories in photojournalism, other times in corporate photographs.

During the past few months, my work has taken me to the Amazon in Brazil and Lake Turkana in Kenya. In both countries I have worked for Aid to the Church in Need (ACN), a Vatican foundation that helps financially the initiatives of various institutions of the Catholic Church. Sometimes in a refugee camp, other times in a clinic for AIDS patients. Places where I discover stories that bring me closer to death, but where what I really understand better is life. In the end, I would like the stories below to help you understand something about the meaning of life…and always with hope.

1. Where God weeps

“Abandon all hope, you who enter here” (Dante, The Divine Comedy)

March 2017. In the peripheries surrounding the city of Sao Paulo, men and women easily succumb to temptations. Yet a group of ex-drug addicts is struggling to reach the shore of normality. They live in Fazenda de la Esperanza [Hacienda of Hope], a pioneering center for ex-addicts. There they seek rehabilitation through life in common, work and spiritual counseling. Fazenda de la Esperanza was started in 1983 by Fray Hans Stapel, a German Franciscan priest, in Guaratingueta, Brazil, to rehabilitate addicts. In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI visited this center during his apostolic trip to Brazil. Fray Hans founded a total of 112 Fazendas de la Esperanza all over the world (Angola, Russia, Germany, Argentina, South Africa, Mozambique…). This year, 2017, another ten new fazendas will open.

—When a drug addict hits bottom rock and decides to try to climb out, we call it the “cry” of the Gospel: my God, my God, why have you forsaken me? It is the cry of despair of the person who is suffering. At that moment, many decide to come to the fazenda freely, says Daniel, a young optimist, who accompanies Rafael, a junkie.

—Look, there is a nuance. You have to understand that drugs are not the origin. The drugs are a consequence of an emotional, family or sexual drama, which arose in the past and needs to be purified…. Daniel is silent and waits for Rafael to speak. An hour later, Rafael recounts his story good-naturedly as darkness falls. Dressed in blue jeans and Nike sneakers, he looks like he has never broken a plate in his life and could pass as the perfect son every mother-in-law wants for her daughter: a quiet and affectionate boy.

These are the appearance, but now his inner life:

“My parents were distant cousins and they got intimate one night in the heat of a campfire in Portoalegre. When my uncle learned that my mother was pregnant, he tried to pierce her belly with a knife.

—This child is mine’ she said, a pretty 16 year old girl with green eyes and blond hair.

—But when I was born, my mother never gave me her blessing. I was a living aborted child and she abandoned me with my grandmother. When I was six, that woman, my mother returned…

—Rafael, you are useless. I expect you to clean the bathroom after I use it, do you understand? That’s what she told me. Normally, I obeyed to avoid being punished.

The boys in the neighborhood called me “disaster face” and the constant humiliation left me friendless. In school, Paulo made my life miserable. Each day he would shout to me: “Your mother is a bad woman and you will end up like her….”

In 2006, tired of the humiliation, I ran away from home. My mother wasn’t interested in finding me and only my grandmother, when she knew where I was, came to bring me home. But I refused. My grandmother, who saw my wounds, understood very well my pain and inner anger.

—I won’t live with that woman, I said

So, at the age of 12 I started working on the streets of Portoalegre selling DVD for the mafia. Small drug dealers gave me a place to sleep. Money was easy to make but was also spent quickly on alcohol and other vices. Without hope in my life, I started to take cocaine at age 13. Every day, every morning, I took 10 grams to get high to sell the DVDs. The drugs gave me euphoria and a carefree feeling. At 16, I started using crack, which was cheaper and left me even more dependent.

In the middle of the chaos, one night I met a new friend, Raul. I knew of his fame and didn’t need to ask about him. I simply accepted him as you accept the first person who enters your life as a friend. We talked and drank. Two days later, Raul asked me for a favor. I took him on a motor bike. We arrived at the destination in ten minutes with two plastic bags. I watched the street with the engine running while my friend grabbed a backpack. He climbed the stairs of a bar, opened the door and took a 38mm pistol from the plastic bag and shot a drug dealer seated in the gambling den. There were shouts in the street, and suddenly among the people in the crowd I recognized Paulo, my old school bully, who was now a big arms dealer. I ran up to him and shot him in cold blood.

Raul carried out 20 more hits as a hired assassin before being executed by a gang, in our apartment. I barely managed to save my own skin.

In a panic, I decided to abandon everything and leave for another city. Only my grandmother knew my whereabouts. Drugs kept me going until a builder offered me a job as a bricklayer. It was hard to keep a schedule, wake up very early and obey someone, when your life is built without rules. But at least I was busy.

One morning, we were sent to repair the roof of a parish church. I wasn’t baptized or a Catholic, but the priest who celebrated Mass was a good man. One day the priest stopped me and said; “If you are a drug addict, I can help you.” God was giving me an opportunity and I wasn’t going to let it escape.

Then I made the second biggest decision in my life. I decided to go to La Fazenda de la Esperanza to get cured. I called my grandmother.

—I am happy you are going there. When I was about to end the call, I heard the voice of a woman on the other end, my mother.

—Don’t cut me off. I need to tell you something that weighs heavily on me. I beg for pardon for all the past years. I love you for what you are going to do now, my son

I hung up. In 22 years, I have never been called a son.

For a year now I have been living at La Fazenda de la Esperanza, gradually escaping from my drug addiction. Healing comes through living alongside others, working and growing in my spiritual life. I have come to understood that my mother has also suffered a lot and I have been able to forgive her. I want to go back to see her because I need a family. I also want to ask my mother to forgive me for what I have done. Then I want to come back to the fazenda to help the others here and also close a cycle in my life. I also have to go and ask for pardon from the parents of the person whose life I ended, even though I know that in Brazil the spirit of vengeance is very strong: an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. I leave my forgiveness to God. I feel he has forgiven me and I can help others to experience his forgiveness. I have been baptized and confirmed and received Holy Communion, but I know that I need prayers to face this. I need to know that I am not alone.

2. About the living and the dead

“The stories are hard, but there is nothing harder or less sentimental than Christian realism” (Flannery O’Connor, The Habit of Being).

March 2017. In the 1970s, many people went to seek diamonds in the central western state of Mato Grosso, in Brazil. Mato Grosso is a region twice the size of Spain or Kenya (900,000 sq. km)

The diamonds attracted many adventurers to Juina, a small city with 50,000 habitants. As a result of greed, there were many murders and the mortality rate was quite high. A local businessman decided to open a funeral home to make his own fortune. Rich and poor had to pay 3000 reales to this sole undertaker in the city.

There came a time when the not so wealthy couldn’t afford the burial fees. The Salesian Bishop of the city, having been informed of the plight of the poor, saw that he needed to care for the indigent people who died, by promoting the work of mercy burying the dead.

Thanks to his initiative and funding provided by Aid to the Church in Need, a second funeral home and mortuary chapel was opened in 2012. Since then, the association under the auspices of the Catholic Church has buried more than 2,500 persons with professionalism, care and respect for the deceased, thanks to many volunteers who take turns in helping the foundation. Those who die in Juina can now be buried for only 500 reales.

Today has been a tough day: documenting the funeral of an old woman and a man murdered by seven stab wounds. The first deceased was a good lady, an evangelical Protestant. The murdered person was a man without faith, who was executed in a quarrel on a farm.

I have seen other morgues around the world and I was impressed by the care with which the volunteers cleaned the man’s body, as you can see in the image above. You see Christ’s universal, catholic charity being extended to this old woman and the murdered man when it was least expected. Perhaps they only hoped for the justice of a dignified burial; but they received the mercy of love.

3. Death, where is your sting?

“I’m interested in the future because that’s where I am going to spend the rest of my life” (Woody Allen)

June 2016. Turkana is an African region in northern Kenya. Lake Turkana is famous for being the largest alkaline lake in the world and an important breeding ground for crocodile. Other deadly species roam the desert, like snakes and spiders, although the most dangerous is the female anopheles mosquito that transmits malaria. The Turkic tribe that surrounds the lake is distinguished by its sinewy tobacco-chewing men and the women who adorn their necks with striking colored collars.

I am dazed as I return from the burial of a year-old child. The dead baby was wrapped in a bag and deposited in the trunk of the car, although I only became aware of this when the priest asked me to take the sack from the back of the vehicle.

“What’s inside…?” I ask.

The priest keeps silent and moves forward offering words of consolation to the mother, who comes to receive us. The villagers finish digging a grave next to the family hut. I let down the little sack and walk away. A nun now consoles the mother who has lost her second child in three years. The ceremony begins with everyone around the sack in the pit: “You are dust and unto dust you will return.” The elderly women of the village prepare to cover the pit with branches. One of them lifts a palm branch and a scorpion appears and runs away rapidly, reminding us that death is still present with us and not just with the tiny child. The old woman, with her necklaces, shows no fear. With a quick strike of her thong, she kills the scorpion, crushed on the sand.

While thinking about life and death, I return to the house and find Erik there, a cheerful Turkic adolescent, who opens the gate for me as I look for some water to hydrate myself.

—Erik, I need a conceptual photo for a project. I need a scorpion and I don’t know where to find one, I tell him

Erik looks at me with quiet disdain and says: “Surely, Musungu’ (white man). I will find it. Do you want it dead or alive?"

I look at him in surprise, because what is terrifying to me holds no fear for him.

—But I don’t want you to take any chances, I insist.

—Relax, Musungu, no problem for me.

Twenty minutes later, Erik knocks at my door. He has a scorpion in the bottom of an empty plastic water bottle that is displaying its stinger.

—Here you are.

And here again is death, here at the bottom of a bottle is death mirrored in a scorpion, which challenges us with its sting. Why the fear of death? Who is the guardian of my life? We aren’t immortals in this life and someone is watching over us. We assume that evil will not prevail.

Erik looks at me. He knows that life and death are daily scenes in Turkana, in Kenya, in Africa. Here, both life and death are cheap. To Africans, it doesn’t make sense the way we westerners clutch so tightly to life. Everything is in God’s hands and his providence.

For Erik, life means simply living for today, and not worrying about tomorrow. Help those you can today, and leave the future to God and his plans.

4. Take my photo for the Pope

“You did not anoint my head with oil, but she has anointed my feet with ointment. Therefore I tell you, her sins, which are many, are forgiven, for she loved much; but he who is forgiven little, loves little.”And he said to her, “Your sins are forgiven” (Lk 7:46-48)

In the central district of Sao Paulo, Brazil, God is with you 24 hours of the day. Amid the skyscrapers and office buildings stands Our Lady of Good Death, a church where the Blessed Sacrament is exposed 24 hours each day. Here in the neighboring peripheries of the city true hope is being born: drug addicts, people without families and prostitutes come to the church to pray. They come alone or accompanied by missionaries of Schoenstatt, who seek out and assist the poor and rejected in society.

Edilson is one of the poor, who lives in a cardboard house. Bruna is a young blonde girl, a consecrated member of Schoenstatt, who visits him every Friday with a group of young people. Edilson doesn’t stop talking.

—I’m going to tell you the truth; she is the only person who visits us without worrying whether we smell good or bad. Many Fridays she comes to accompany us and ask about our lives. She doesn’t care about our appearance. She is the only person who remembered my birthday and brought me a cake to celebrate.

—Well, I can be with you for a few hours, but God is with you for 24 hours, says Bruna

—My dream is to meet the Pope and take a picture, interrupts Rafinha, crippled by an accident and the father of seven children. Take a photo of me and bring it to him, he implores.

—I will try…

5. Look people in the eyes

“Giving love is in itself an education” (Eleanor Roosevelt)

“If your photograph isn’t good enough, then you’re not close enough,” says war photographer Robert Capa. Something similar can be said about mercy.

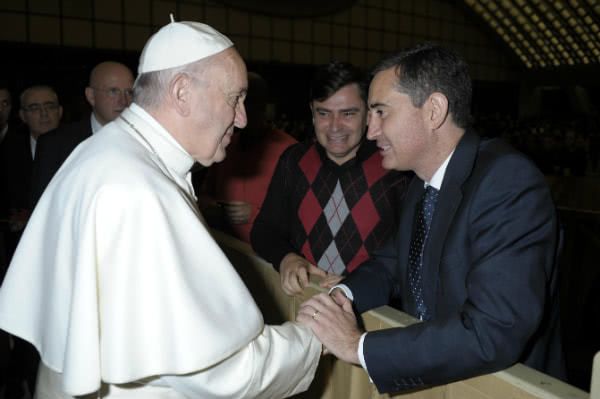

Rome, 1 February 2017. Holy Father, I am Ismael, a Spanish photographer who lives in Kenya. I assist the project Aid to the Church in Need. We have an album of photos to give you, but how do we give hope to these people?

—[pensive] Treat them with affection, with your look, with a gesture of tenderness. Look them personally in the eye and you will bring hope.

—Thank you Holy Father, I will try to do so and pray for your intentions at Mass each day, as I am a member of Opus Dei.

—Oh and in Kenya! Do you live there? In Kenya, you are doing a great job. The Work is doing a great job there. When I was in Kenya last year, I could see all that is being done in many places, with people from all classes. Keep up the good work. Opus Dei is doing a great job in helping Kenyans.

—Thank you Pope Francis. I don’t think it’s any merit of Opus Dei’s. We’re just trying to help you and the people there.

Rome, 17 September 2016. This time I don’t present Bishop Javier Echevarria with any more stories about Africa in the get-together, but I take out a crocodile tooth from my pocket

—You didn’t take it from the crocodile yourself?

—A sage in northern Kenya gave it to me, in the Kakuma refugee camp. I’ll put it alongside my passport so you may bless my visa; sometimes when it has expired I’ve had problems with the African bureaucracy.

—Ismael, my son, I’ll bless whatever you want, of course. But be careful with the crocodiles; we need you alive. The most important passport for a Christian is the one that gives entrance to heaven. So take care, you are still very young. And while we are on earth, we are here to give consolation and life to the others. As Saint Josemaria taught, “the time has ended for giving a few spare coins and old clothes. We have to give affection; we have to give our heart!”