Education in East Africa in 1958

In part these obstacles were due to the legal framework in force at the time. Some of the highlights fro the Education Ordinance of 1924 include:

- It created three advisory committees to deal with European, Asian and African education.

- All schools and teachers were to be registered.

- The content of education for each race was different.

- The Director of Education was to be given power to inspect all the schools and to close any if necessary.

- All schools had to follow the same basic regulations regardless of race though the content of education for each race was different.

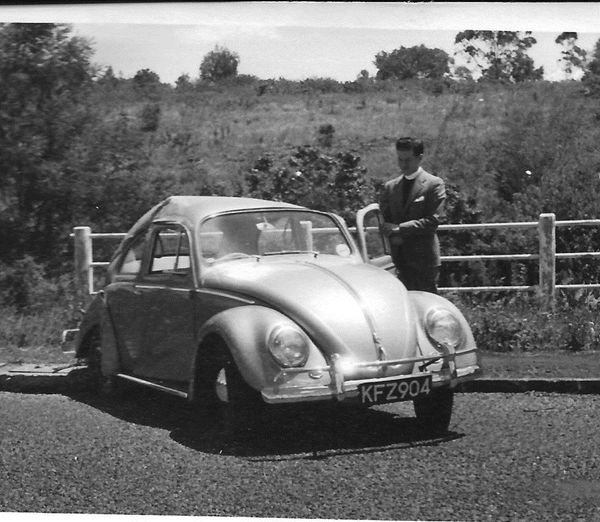

Fr. Casciaro in Nairobi

Soon after arriving, Fr. Casciaro contacted Msgr. Mojayski, the Apostolic Delegate. The Monsignor had been Apostolic Delegate in Mexico and there he had struck up a very close friendship with Fr. Casciaro. He was delighted that his old friend had come to Kenya to see him and said he was very much looking forward to their meeting. Don Pedro’s first aim was to explain in detail the reasons Msgr. Escrivá had to think that the starting of a Catholic university in East Africa was not feasible at that moment.

In their discussions Don Pedro pointed out at the main difficulty: in Great Britain the establishment of a university required a Royal Charter. It was the Privy Council which studied the matter and drafted a Charter to be presented to the Monarch for signature. Once the university was established, it was independent and enjoyed freedom from civil authorities. The Government provided funds and very carefully avoided giving any suspicion of interfering in the autonomy of universities.

Although British society and institutions were foreign to the apostolic Delegate, he had been in the diplomatic world for many years and understood the very serious difficulties involved in obtaining a Royal Charter. The negotiations would take years and, given the urgency of the educational need, the delay would render the project useless. Fr. Casciaro emphasised that, on the other hand, the idea of a pre-university course had the advantage of coming from the Colonial Government itself. He summarised for Msgr. Mojaisky the Government’s plans following Makerere College decision to discontinue their preparatory courses. The Government’s plans were that, out of an annual intake of 120 students to be trained in Kenya, 40 would be coming from the facilities provided for the Catholics. The course would be spread over two years, so that, after the first year there would be a turnover of around 80 students. Evidently, the colonial authorities thought that these figures would cover the numbers of students with adequate academic capacity which secondary education could provide for the time being.

Meanwhile, lawyers and accountants established courses for the granting of their own qualifications with recognition from their own national professional bodies. On the other hand, many years after our study of the possibilities of starting a university, Buckingham University made a start as a private university and after some time it granted degrees.

Don Pedro had made it clear to his friend the Apostolic delegate that we should “point out and explain to the authorities, right from the start, the secular nature of the members of Opus Dei and that this was not a mission school; nor were the teachers missionaries but secular, professional people with the appropriate academic qualifications, who were practising their respective professions in full freedom.”(cf. Gabiola, ut omnes… p. 61)

By 28th October Don Pedro was back in Rome, and celebrated there the election of the new Pope, John XXIII.

St. Josemaría’s impulse

Soon before he died of cancer in 2009, someone asked Kevin O’Byrne how involved was St. Josemaría in the beginnings of Strathmore College. His answer was: there were periods in which we would talk with him on the phone every day. He could not have got more involved.

St. Josemaria, when visiting a country, would say: “I have come to see you and to learn. I am in your country looking forward to learning”. Don Alvaro did the same, very especially in his trip to Nairobi in 1989. He taught his children going to new countries to do the same: “When going to Kenya, therefore, we had to be ready to learn about our new country. There was not the slightest doubt about it, and we were gladly and wholeheartedly prepared to do it. But, then, we found that, in spite of our willingness, a deep grasp of things was not easy” remembers Fr. Gabiola in his Memoirs.

Africa

In those days, information about Africa was scarce and not always reliable.

“This difficulty in learning was, I think, the greatest barrier to our work and I now feel that our Founder knew it. Well aware of the need of first-hand knowledge, he hurried us to be on the ground without any wasted time. This was helpful but, all the same, when we arrived in Nairobi, there was practically no difference; we could not find a way to approach directly the African population or its culture; we were surrounded by Europeans in such an appalling way …” (Gabiola, Ut omnes…, 42)

Although five years had gone by since the beginning of the Mau-Mau problem when the people of the Work arrived in Nairobi, the emergency period had not yet ended and the real facts behind the conflict were not totally public at that time. While in Nairobi, Kikuyu men needed to carry pass books which had been issued to them in the fashion of some so-called “green books” of earlier times. There was in Nairobi among the Europeans curiosity about Jomo Kenyatta especially after his arrest in October 1952. People who were not born sixty years ago may find some facts and views about Kenya in the late 50’s possibly striking.

St. Josemaria had told us:

“We must be prepared to work from Pole to Pole with the affection of self-giving, with the love that soothes out all frictions. We will be, we will willingly make ourselves, of the race, of the colour, of the manner — whatever it might be — that exists in the country where Jesus Christ sends us to. And all this from the depth of our heart, and without ceasing to love very much our country of origin”. (Obras X-1957, p.10).

By the end of that same year, they had already set up the first centre of Opus Dei in Africa, and as St. Josemaria has always taught his children, the best room in the house was reserved as the Chapel with a tabernacle.The items for the Oratory that had been bought in Madrid arrived in Mombasa in November 1958. Soon the Oratory was set up at the end of the corridor of the upper floor, as it was the safest place of the house.

The reredos of that first Oratory was an image of our Lady, nicely framed in gilded carved wood, bought in a Sikh’s shop in town.

Fr O’Meara

The Catholic Bishops had delegated many of their dealings with the Colonial Government to Father Frank O’Meara, Holy Ghost Father, in his capacity of General Secretary of Education for Catholic Missions.

His task included finding out the wishes of the Hierarchy on educational matters and then negotiate with the corresponding Department in the Ministry of Education on the lines laid down by them. This meant that all negotiations had to go through Fr. O’Meara which was not satisfactory as the new comers brought many new ideas Fr. O’Meara was not prepared for.

Fr. O’Meara saw Strathmore plans in the light of his many years of experience in East Africa and understood them as long term targets; but they were very short term targets.

In 1958, most people believed that independence would take at least fifty years to come. Things had never moved very fast in the colonies. Matters, which for us seemed to be urgent targets, were for Fr. O’Meara and many others, ideals or, at best, guidelines for a life-long project. Fr. O’Meara never saw any problems with the project we were putting forward because he always thought that many of its characteristics were impossible.

First Trip to Uganda December 1958

Ed Hernandez and Fr. Gabiola took a Volkswagen and drove North West across the Rift Valley into Nakuru and Eldoret, and arrived in Jinja, at the Northern coast of Lake Victoria.

“It was a useful visit, because it gave us a sense of the sort of thing we had to be prepared to build if we wanted to prepare students for Makerere” says Fr. Gabiola in his memoirs.

According to Fr. Gabiola, Uganda had an older African tradition; some of the tribes there had developed into societies of more complex structures than the tribes in Kenya; missionary work had also been started in Uganda some fifty years or more before Kenya. In addition, we had in mind meeting friends of our friends in Nairobi.

We reached Kampala, the capital of Uganda, with curiosity. The Baganda, who occupy all the land west of Lake Victoria around Kampala, have always been held as the aristocratic people in East Africa. As it happens in a few other areas of the Continent, this tribe possesses a monarchical structure.

There are in the capital a number of hills, supposedly to be seven, which, together with other reasons, make Catholics think of the Capital of Uganda as the Rome of Africa. On top of hills three Cathedrals, two Catholic and one Anglican, and one Mosque are built.

A plot of land in Nairobi

First it was decided the new College had to be near the City, among other things because we intended to have non-resident students as well.

Secondly the plot of land had to be in a non-restricted area (i.e., open to all races) and that limited tremendously the options.

Very soon it was clear that the only possible land was the one of the archdiocese along St. Austin’s Road (today James Gichuru Road). It was part of the huge extension of land which the Catholic mission had been allocated very early in the history of Nairobi. Much of it had been sold for development, and pieces of several sizes had been dedicated to Catholic institutions, such as St Mary’s School for boys, Loreto Convent Msongari, for girls and, of course, the Archbishop’s House itself.

Before identifying this land of the Archdiocese, they had tried to get a 20 acre plot belonging also to the Archdiocese near Gitanga Road. The European neighbours rejected the application in a very unpleasant meeting at the City Council (January 1960) because they didn’t want a School (for Africans) in their vicinity. In practice, Nairobi was a racially segregated town.

Then they talked again with Archbishop McCarthy and he made available, at market price, up to 40 acres near his house, next to St Mary’s School (the house of the Archbishop was in St. Mary’s compound).

It just so happened that around that time, Fr Joseph had an accident, and rolled the car over near the bridge of James Gichuru (then St. Austin’s Road), very close to the place where the Archbishop had offered 40 acres of land, next to his own house. He spent a few hours there and realized the piece of land was very good.

But the Archbishop offered the land at market price (£30,000 a huge amount of money at that time) as the Archdiocese needed that money badly.

The negotiations were closed by March 1960.

The new plot of land was set between St. Austin Road, Strathcona Road and Riverside, with the Nairobi River to the north of the property.

On visiting the plot, Don Pedro Casciaro, an architect, immediately suggested a possible distribution of the area, with the main buildings in the higher part of the plot, just as the local architect, Ed Hernandez, had thought before.

It was at this time that the name of Strathmore started being used, taken from the road on the south side of the property.

Winds of Change

Early in February 1960, Harold Macmillan had given the historical “Winds of change” address in Cape Town; the world started heralding the end of the British Colonies.

Also in 1960 the Belgian Congo experienced some very tragic developments with the Katanga War; most Europeans fled the country. And that happened just one month after the first women of the Work had arrived in Kenya in August 1960.

Strathmore Construction

Soon Ed and Kevin rented some office space and set up an architect’s office to build the new College. They set June 1960 as the deadline to go to tenders, as the College was supposed to be ready for February 1961.

The contract for the construction of the first phase was signed on 16th July 1960, and the works started next day.

There was some discussion regarding the name of the new College (African name?); little by little the name Strathmore was chosen.