1. God's revelation of himself to mankind

“It pleased God, in his goodness and wisdom, to reveal himself and to make known the mystery of his will (see Eph 1:9). His will was that men should have access to the Father, through Christ, the Word made flesh, in the Holy Spirit, and thus become sharers in the divine nature (see Eph 2:18; 2 Pet 1:4). By this Revelation, then, the invisible God (see Col 1:15; 1 Tim 1:17), from the fullness of his love, addresses men as his friends (see Ex 33:11; Jn 15:14-15), and moves among them (see Bar 3:38), in order to invite and receive them into his own company" [1] (see Catechism of the Catholic Church [CCC] 51).

God's revelation starts with creation itself, where he offers a perennial witness to himself (CCC 288). [2] Through creatures God manifests himself to people of all times, making his goodness and perfections known. Among these creatures the human being, being the image and likeness of God, is the creature that most fully reveals Him. Nevertheless, God has wished to manifest himself as a personal Being through the history of salvation, by raising up and guiding a people to be the custodian of his revealed word, and to prepare through that people for the Incarnation of his Word, Jesus Christ (see CCC 54-64). [3] In Christ, God reveals the mystery of his Trinitarian life. He reveals the Father's plan to recapitulate all things in his Son and to choose and adopt all men and women as children in his Son (see Eph 1:3-10; Col 1:13-20), gathering them together to share in his divine life through the Holy Spirit. God reveals himself and carries out his plan of salvation through the missions of the Son and the Holy Spirit in history. [4]

The content of Revelation includes both natural truths that we can discover by human reason alone, and truths that exceed the grasp of human reason and can only be known by the free and gratuitous goodness of God who reveals them. The principal subject matter of divine Revelation is not abstract truths about the world and mankind, but rather God's self-revelation of the mystery of his own personal life and his invitation to share in it.

Divine Revelation is carried out “by deeds and words which are intrinsically bound up with each other" [5] and shed light on each other. “By revealing himself God wishes to make [men and women] capable of responding to him, and of knowing him, and of loving him far beyond their own natural capacity" (CCC 52).

In addition to the works and external signs by which he reveals himself, God grants the interior impulse of his grace to enable us to adhere wholeheartedly to the truths revealed (see Mt 16:17; Jn 6:44). This intimate Revelation of God in the hearts of the faithful should not be confused with so-called “private revelations," which are occasionally given to select individuals. Although accepted as part of the Church's tradition of holiness, these do not transmit any new and original content but rather remind the faithful of the unique revelation by God carried out in Jesus Christ and exhort them to put it into practice (see CCC 67).

2. Sacred Scripture, witness to Revelation

The people of Israel, over the course of centuries and under God's inspiration and direction, put into writing the testimony of God's revelation in their own history, which they directly connected with the revelation given to Adam and Eve. In addition to the Old (or First) Testament , the Scriptures of Israel that would be embraced by the Church, Christ's apostles and the first disciples also put into writing the testimony of God's revelation as it has been fully accomplished in the Word, as witnesses to his earthly journey, especially the Paschal Mystery of his death and resurrection. Their writings gave rise to the books of the New Testament .

The truth that the God to whom Israel's Scriptures testify is the one true God, creator of heaven and earth, is made especially clear in the Wisdom Books. The content of these books transcends the confines of Israel and displays an interest in the common experience of the human race confronting the great issues of existence. The topics range from the meaning of the universe to the meaning of man's life ( Wisdom ); from questions about death and what comes after it, to the significance of man's activity on earth ( Qohelet/ Ecclesiastes ); from family and social relationships to the virtues which should govern them in order to live in accord with the plans of God the Creator and thus achieve the fullness of one's own humanity ( Proverbs, Sirach , etc).

God is the author of Sacred Scripture. The sacred writers (hagiographers), who have written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, are also authors of the text. For the composition of the sacred books, “God chose certain men who, all the while he employed them in this task, made full use of their own faculties and powers, so that, though he acted in them and by them, it was as true authors that they consigned to writing whatever he wanted written, and no more" [6] (see Catechism 106). Everything that the sacred writers affirm can be considered as affirmed by the Holy Spirit: “we must acknowledge that the books of Scripture, firmly, faithfully and without error, teach that truth which God, for the sake of our salvation, wished to see confided to the Sacred Scriptures." [7]

To understand Sacred Scripture correctly, one needs to take into account two senses of Scripture: the literal and the spiritual, the latter being subdivided into allegorical, moral and anagogical senses. One must also take into account the various literary genres in which the sacred books, or parts thereof, have been composed (see CCC 110, 115-117). Sacred Scripture should always be read in the Church , that is, in the light of her living tradition and the analogy of faith (see CCC 111-114). Scripture should be read and understood in the same Spirit in which it was written.

Scholars who endeavor to interpret and go deeper into the contents of Scripture base the authority of their studies on their own academic authority. The Church's Magisterium, on the other hand, has the responsibility of formulating authentic interpretations binding on the faithful, based on the authority of the Spirit who assists the teaching ministry of the Pope and the bishops in communion with him. Thanks to this divine assistance, from the first centuries the Church identified the books containing the testimony of Revelation, in both the Old and New Testaments, thus drawing up the “canon" of Sacred Scripture (see CCC120-127).

Accepting the different senses and literary genres found in Sacred Scripture is necessary for interpreting correctly what the sacred writers say about aspects of the world that pertain to the natural sciences. These include the formation of the cosmos, the appearance on earth of different life forms, the origins of human life and natural phenomena in general. A “fundamentalist" interpretation of every passage in Scripture as a literal, historical event should be avoided, when other interpretations are possible. One should of course also avoid the error of those who interpret the biblical narratives as purely mythological, lacking in historical content or any information about God's direct intervention in the events described there. [8]

3. Revelation as the history of salvation culminating in Christ

As a dialogue between God and mankind in which God invites us to share in his own life, revelation from its beginnings is seen as a “covenant" that gives rise to a “history of salvation." “And furthermore, wishing to open the way to heavenly salvation, he manifested himself to our first parents from the very beginning. After the fall, he buoyed them up with the hope of salvation, by promising redemption (see Gen 3:15); and he never ceased to take care of the human race. For he wishes to give eternal life to all those who seek salvation by patience in well-doing (see Rom 2:6-7). In his own time God called Abraham, and made him into a great nation (see Gen 12:2). After the era of the patriarchs, he taught this nation, by Moses and the prophets, to recognize him as the only living and true God, as a provident Father and just judge. He taught them, too, to look for the promised Savior. And so, throughout the ages, he prepared the way for the Gospel." [9]

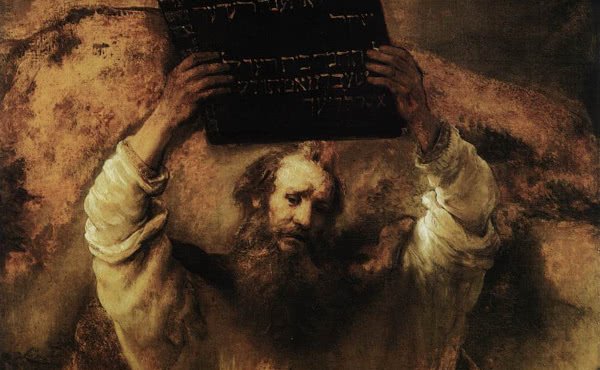

The covenant of God with mankind began with the creation of our first parents and their elevation to the life of grace, enabling them to share in God's intimate life. The covenant was continued with God's cosmic pact with Noah, and explicitly revealed to Abraham and later, in a special way, to Moses, to whom God gave the Tablets of the Covenant. Both the numerous offspring promised to Abraham, in whom all the nations of the earth would be blessed, and the law entrusted to Moses with the sacrifices and priesthood that accompanied divine cult, are a preparation and figure of the new and eternal covenant in Jesus Christ, Son of God, made a reality by his Incarnation and paschal Sacrifice. The new covenant in Christ redeems us from the sin of our first parents, whose sin of disobedience broke off the first offer of a covenant on the part of God the Creator.

The history of salvation is manifested as an all-embracing divine pedagogy pointing to Christ. The prophets, sent to remind the people of the covenant and its moral demands, speak clearly about the promised Messiah. They announce the new covenant, both spiritual and eternal, to be written on the hearts of believers. Christ will reveal it with the beatitudes and all his teachings, promulgating the commandment of charity, the fullness of the Law.

Jesus Christ is simultaneously the mediator and the fullness of Revelation. He is both the Revealer and the Revelation, as the Word of God made flesh: “In many and various ways God spoke of old to our fathers by the prophets; but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world" ( Heb 1:1-2). God, in his Word, has said everything and in a definitive way. “The Christian economy, therefore, since it is the new and definitive covenant, will never pass away; and no new public Revelation is to be expected before the glorious manifestation of our Lord Jesus Christ" [10] (see CCC 65-66). Divine Revelation is accomplished and brought to fulfillment especially in Christ's Paschal mystery, in his passion, death and resurrection. This is God's “definitive word" on the immensity of his Love and his determination to renew the world. It is only in Jesus Christ that God reveals man to himself and enables us to understand our true dignity and lofty vocation. [11]

Faith, considered as a virtue, is man's response to God's revelation; it is a personal adherence to God in Christ, moved by Christ's words and deeds. The credibility of this Revelation rests, above all, on the credibility of the person of Jesus Christ, indeed on his whole life. His role as mediator, as the fullness and ground of the credibility of Revelation, distinguishes the person of Jesus Christ from the founder of any other religion. Founders of other religions do not claim to be, in their own person, the fullness and accomplishment of what God wishes to reveal, but only to be a mediator who will lead others to this revelation.

4. The transmission of divine Revelation

Divine revelation is contained in Sacred Scripture and Tradition, which together constitute one sole deposit where the word of God is preserved. [12] “Flowing out from the same divine well-spring," the two are interdependent. Tradition transmits and interprets Scripture, and Scripture in turn verifies and confirms whatever is passed on in Tradition (see CCC 80-82). [13]

Tradition, based on the preaching of the Apostles, testifies to and transmits in a living and dynamic way what Scripture has set down in a fixed text. “The Tradition which comes from the apostles makes progress in the Church, with the help of the Holy Spirit. There is a growth in insight into the realities and words that are being passed on. This comes about in various ways. It comes through the contemplation and study of believers who ponder these things in their hearts (see Lk 2:19 and 51). It comes from the intimate sense of spiritual realities which they experience. And it comes from the preaching of those who have received, along with their right of succession in the episcopate, the sure charism of truth." [14]

The teachings of the Church's Magisterium, the Church Fathers, liturgical prayer, the common view of the faithful who live in God's grace, and also daily realities such as the teaching of the faith by parents to their children or through Christian apostolate, all contribute to the transmission of divine Revelation. In fact, what was received by the Apostles and transmitted to their successors, the Bishops, comprises “everything that serves to make the People of God live their lives in holiness and increase their faith. In this way the Church, in her doctrine, life and worship, perpetuates and transmits to every generation all that she herself is, all that she believes." [15] The Church's “great apostolic Tradition" should be distinguished from the various traditions, whether theological, liturgical, disciplinary, or devotional, whose value can be quite limited and even passing (see CCC 83).

Divine revelation comprises both truth and life. Not only a body of teachings but also a way of life is transmitted: doctrine and example are inseparable. What is transmitted is a living experience, an encounter with the Risen Christ, and what that event has meant and continues to mean for the life of each person. Consequently, when speaking of the transmission of Revelation, the Church speaks of fides et mores , life and customs, doctrine and conduct.

5. The Church's Magisterium, guardian and authorized interpreter of Revelation

“The task of giving an authentic interpretation of the Word of God, whether in its written form or in the form of Tradition, has been entrusted to the living teaching office of the Church alone. Its authority in this matter is exercised in the name of Jesus Christ." [16] The Church's “living teaching office," made up of the bishops in communion with St. Peter's successor, the bishop of Rome, is a service rendered to the word of God and has as its aim the salvation of souls. Therefore, “this Magisterium is not superior to the Word of God, but is its servant. It teaches only what has been handed on to it. At the divine command and with the help of the Holy Spirit, it listens to this devoutly, guards it with dedication and expounds it faithfully. All that it proposes for belief as being divinely revealed is drawn from this single deposit of faith." [17] The teachings of the Church's Magisterium are the most important place where there the apostolic Tradition is found. With respect to this tradition, we could say that the Magisterium is, as it were, its “sacramental dimension," that is, its outward, visible expression.

Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition and the Magisterium of the Church constitute, therefore, a certain unity, such that no one of the three can exist on its own. [18] The foundation of this unity is the Holy Spirit, Author of Sacred Scripture, protagonist of the living Tradition of the Church, guide of the Magisterium, which he assists with his charisms. The Protestant Reformation churches from the very beginning wished to follow the principle of sola scriptura , leaving scriptural interpretation in the hands of individual believers. This position has given rise to the great dispersion of Protestant denominations and has turned out to be well-nigh unsustainable. Every Scripture text requires a context, specifically a tradition, from which it is born and in which it is read and interpreted. “Fundamentalism" also tries to separate Scripture from Tradition and the Magisterium, erroneously seeking to maintain a unity of interpretation by adhering exclusively to the literal sense (see CCC 108).

The Church, in teaching the contents of the revealed deposit of faith, possesses infallibility in docendo (when she teaches),based on the promises of Jesus Christ with regard to her indefectibility, which enables her to carry out unfailingly the mission of salvation entrusted to her (see Mt 16:18; Mt 28:18-20; Jn 14:17-26). This infallible teaching office is carried out:

a) when the Bishops gather together in an ecumenical Council in union with the successor of Peter, head of the Apostolic college;

b) when the Pope promulgates a truth ex cathedra , or when by using a form of expression and type of document that makes explicit reference to his universal Petrine mandate, he promulgates a specific teaching which he considers necessary for the good of the People of God;

c) when the Bishops of the whole Church, in union with the successor of Peter, are unanimous in professing the same doctrine or teaching, even though they are not gathered together in one place. Although a bishop who sets forth on his own a specific teaching does not enjoy the charism of infallibility, the faithful are equally obliged to a respectful obedience. Just as they should observe the teachings coming from the College of Bishops or from the Pope, even though they are not expressed in a definitive and non-changeable manner [19] .

6. The unchangeable nature of the deposit of Revelation

Dogmatic teaching in the Church has existed from the very first centuries of the Christian era (the word dogma simply means 'doctrine' or 'teaching'). The principal elements of what the Apostles preached were put into writing and thus gave rise to the professions of faith asked of all those seeking baptism. These “professions of faith" helped define the identity of the Christian faith. The dogmas or teachings grew in number as the Church herself grew. This growth was not because of any need to change or increase what had to be believed, but rather because often some new need arose to confront a specific error or strengthen the faith of the Christian people by examining a question more deeply and defining a specific point clearly and precisely. When the Church's Magisterium sets forth a new dogma it is not creating something new, but rather simply explaining what is already contained in the revealed deposit of the faith. “The Church's Magisterium exercises the authority it holds from Christ to the fullest extent when it defines dogmas, that is, when it proposes, in a form obliging the Christian people to an irrevocable adherence of faith, truths contained in divine Revelation or also when it proposes, in a definitive way, truths having a necessary connection with these" (CCC 88, revised version).

Dogmatic Church teaching, for example the articles of the Creed, is unchangeable since it presents the contents of a Revelation received from God and not drawn up by men. However, these dogmas allow for a certain harmonious development, whether because of a deeper understanding of the faith that is attained over time, or because of new problems arising in specific cultures and epochs that require a response from the Church in accord with God's word, making explicit what is already implicitly contained there. [20]

Fidelity and progress, truth and history, are not conflicting realities with regard to Revelation. [21] Jesus Christ, uncreated Truth, is also the center and fulfillment of history. The Holy Spirit, Author of the deposit of Revelation, is the One who guarantees its fidelity and also helps mankind to go deeper into its meaning over the course of history, leading the faithful towards the “fullness of truth" (see Jn 16:13). “Yet even if Revelation is already complete, it has not been made completely explicit; it remains for Christian faith gradually to grasp its full significance over the course of the centuries" (CCC 66)

The factors that give rise to the development of dogma are the same factors that give rise to making the living Tradition of the Church more explicit: the preaching of the bishops, study by the faithful, prayer and meditation on the word of God, experience of spiritual realities, and the example of the saints. Often the Magisterium sets forth teachings in an authoritative way that have been previously studied by theologians, believed by the faithful, and lived by the saints. [22]

Giuseppe Tanzella-Nitti

Bibliography

Catechism of the Catholic Church , 50-133

Second Vatican Council, Const. Dei Verbum , 1-20

John Paul II, Enc. Fides et Ratio , 14 September 1998, 7-15

Footnotes

[1] Vatican II, Constitution Dei Verbum, 2.

[2] cf. Vatican II, Const . Dei Verbum , 3; John Paul II, Fides et Ratio , 14 September 1998, 19.

[3] cf. Vatican I, Const. Dei Filius , 24 April 1870, DS 3004.

[4] cf. Vatican II, Const. Lumen Gentium , 2-4; Decree Ad Gentes , 2-4.

[5] cf. Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum , 2.

[6] Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum , 11.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Important guidelines for correctly interpreting Scripture with regard to science can be found in Leo XIII, Providentissimus Deus , 18 November 1893; Benedict XV, Spiritus Paraclitus , 15 November 1920 and Pius XII, Humani Generis 12 July 1950.

[9] Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum , 3.

[10] Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum, 4.

[11] cf. Vatican II, Const. Gaudium et Spes, 22.

[12] “Forgive me for being so insistent, but I must remind you again that the truths of faith are not determined by majority vote. They make up the depositum fidei : the body of truths left by Christ to all the faithful and entrusted to the Magisterium of the Church to be authentically taught and set forth" St. Josemaria, Homily The Supernatural Aim of the Church , in In Love with the Church , 31 (Scepter, London/New York 1989).

[13] cf. Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum , 9.

[14] Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum , 8.

[15] Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum , 8, cf. also, Council of Trent, Decree Sacrosancta , 8 April 1546, DS 1501.

16 Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum , 10.

[17] Ibid.

[18] cf. Ibid.

[19] cf Vatican II, Const. Lumen Gentium , 25; Vatican I, Const. Pastor aeternus , 18 July 1870, DS 3074

[20] “It is good, therefore, that over the course of time, the understanding, knowledge and wisdom of the entire Church and of each of her members should grow and progress. But this growth should follow its own proper nature, i.e., it should be in agreement with the direction of dogma and should follow the dynamism of the one and same doctrine." St Vincent of Lerins, Communitorium , 23.

[21] cf. John Paul II, Fides et Ratio , 11-12, 87.

[22] Vatican II, Const. Dei Verbum , 8 (cf. footnote no. 14 above).